Free Wilde Readings Series Continues with Spring Line-up, Open Mics.

Wilde Readings is a free monthly literary reading series that provides local writers — poets, fiction, non-fiction — a chance to share their work with the community. The format showcases featured authors, as well as an open mic for interested audience members.

The open mic session offers a safe and supportive environment for teens and adults to share writing of all different forms. Open mic presenters are asked to keep their readings to five minutes or less. Come explore how a range of creativity can inspire and fuel the imagination and nurture one’s one craft and well-being.

Wilde Readings is sponsored by HoCoPoLitSo and coordinated by Laura Shovan, Ann Bracken, Linda Joy Burke, and Faye McCray.

Second Tuesdays at the Columbia Association Art Center in Long Reach. Starts at 7 p.m.

Spring featured Reader Line-up:

APRIL 9, 2019

Host: Linda Joy Burke

Bruce A. Jacobs is a poet, author, and musician. He has appeared on NPR, C-SPAN, and elsewhere. His two books of poems are Speaking Through My Skin (MSU Press), which won the Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award, and Cathode Ray Blues (Tropos Press). His most recent nonfiction book is Race Manners for the 21st Century (Arcade/Skyhorse). His work has been published by dozens of literary journals and sites, including Beloit Poetry Journal, Gwarlingo, Truthout, and the 180 More anthology edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins. He lives in Washington, DC.

Bruce A. Jacobs is a poet, author, and musician. He has appeared on NPR, C-SPAN, and elsewhere. His two books of poems are Speaking Through My Skin (MSU Press), which won the Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award, and Cathode Ray Blues (Tropos Press). His most recent nonfiction book is Race Manners for the 21st Century (Arcade/Skyhorse). His work has been published by dozens of literary journals and sites, including Beloit Poetry Journal, Gwarlingo, Truthout, and the 180 More anthology edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins. He lives in Washington, DC.

Bio for Naomi Thiers

Naomi Thiers grew up in California and Pittsburgh, but her chosen home is Washington-DC/ Northern Virginia. She is the author of three poetry collections: Only The Raw Hands Are Heaven(which won the Washington Writers Publishing House award), In Yolo County,and She Was a Cathedral(both from Finishing Line Press.) Her poems, fiction, and essays have been published in Virginia Quarterly Review, Poet Lore, Colorado Review, Grist, Sojourners,and other magazines and anthologies. Former poetry editor of Phoebe, she works as an editor for Educational Leadership magazine and lives in a condo on the banks of Four Mile Run in Arlington, Virginia.

Naomi Thiers grew up in California and Pittsburgh, but her chosen home is Washington-DC/ Northern Virginia. She is the author of three poetry collections: Only The Raw Hands Are Heaven(which won the Washington Writers Publishing House award), In Yolo County,and She Was a Cathedral(both from Finishing Line Press.) Her poems, fiction, and essays have been published in Virginia Quarterly Review, Poet Lore, Colorado Review, Grist, Sojourners,and other magazines and anthologies. Former poetry editor of Phoebe, she works as an editor for Educational Leadership magazine and lives in a condo on the banks of Four Mile Run in Arlington, Virginia.

MAY 14, 2019 — TEEN NIGHT

Host: Faye McCray

Kate Hillyer lives, works, and runs the trails near Washington, D.C. She writes middle grade and young adult fiction, and her essay “Learning to Dance” appears in the anthology Raised by Unicorns. Kate blogs at From the Mixed Up Files of Middle Grade Authors and The Winged Pen, and serves as a Cybils judge for Poetry and Novels in Verse. You can find her on Twitter as @SuperKate.

Kate Hillyer lives, works, and runs the trails near Washington, D.C. She writes middle grade and young adult fiction, and her essay “Learning to Dance” appears in the anthology Raised by Unicorns. Kate blogs at From the Mixed Up Files of Middle Grade Authors and The Winged Pen, and serves as a Cybils judge for Poetry and Novels in Verse. You can find her on Twitter as @SuperKate.

Leah Henderson’s novel One Shadow on the Wall, is an Africana Children’s Book Award notable and a Bank Street Best Book of 2017, starred for outstanding merit. Her short story “Warning: Color May Fade” appears in the YA anthology Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America and her forthcoming picture books include Mamie on the Mound, Day For Rememberin’, and Together We March. Leah has an MFA in Writing and is on faculty at Spalding University’s MFA program.

Leah Henderson’s novel One Shadow on the Wall, is an Africana Children’s Book Award notable and a Bank Street Best Book of 2017, starred for outstanding merit. Her short story “Warning: Color May Fade” appears in the YA anthology Black Enough: Stories of Being Young & Black in America and her forthcoming picture books include Mamie on the Mound, Day For Rememberin’, and Together We March. Leah has an MFA in Writing and is on faculty at Spalding University’s MFA program.

JUNE 11, 2019

Host: Laura Shovan

Wallace Lane is a poet, writer and author from Baltimore, Maryland. He received his MFA Degree in Creative Writing and Publishing Arts from The University of Baltimore in May 2017. His poetry has appeared in Little Patuxent Review, The Avenue, Welter Literary Journal and is forthcoming in several other literary journals. Jordan Year, his debut collection of poetry, is a coming of age narrative, which uncovers what it means to live and survive in Baltimore City. Wallace also works as a Creative Writing teacher with Baltimore City Public Schools.

Wallace Lane is a poet, writer and author from Baltimore, Maryland. He received his MFA Degree in Creative Writing and Publishing Arts from The University of Baltimore in May 2017. His poetry has appeared in Little Patuxent Review, The Avenue, Welter Literary Journal and is forthcoming in several other literary journals. Jordan Year, his debut collection of poetry, is a coming of age narrative, which uncovers what it means to live and survive in Baltimore City. Wallace also works as a Creative Writing teacher with Baltimore City Public Schools.

Jen Michalski is the author of the novels The Summer She Was Under Water and The Tide King (both Black Lawrence Press), a couplet of novellas, Could You Be With Her Now (Dzanc Books), and two collections of fiction. Her work has appeared in more than 100 publications, including Poets & Writers, and has received five Pushcart nominations. She was named as “One of 50 Women to Watch” by The Baltimore Sun and “Best Writer” by Baltimore Magazine. She is the host of a fiction reading series in Baltimore, called Starts Here! and editor of the weekly online literary journal jmww.

Jen Michalski is the author of the novels The Summer She Was Under Water and The Tide King (both Black Lawrence Press), a couplet of novellas, Could You Be With Her Now (Dzanc Books), and two collections of fiction. Her work has appeared in more than 100 publications, including Poets & Writers, and has received five Pushcart nominations. She was named as “One of 50 Women to Watch” by The Baltimore Sun and “Best Writer” by Baltimore Magazine. She is the host of a fiction reading series in Baltimore, called Starts Here! and editor of the weekly online literary journal jmww.

April Wilde Readings to Feature Poets Bruce Jacobs, Naomi Thiers, Open Mic

Howard County’s monthly free reading series continues on the second Tuesday of each month. In April, the reading will feature poets Bruce Jacobs, Naomi Thiers, and an open mic — that means you, bring your work.

Wilde Readings is sponsored by HoCoPoLitSo and coordinated by Laura Shovan, Ann Bracken, Linda Joy Burke, and Faye McCray.

All are welcome, and everyone is encouraged to participate in the open mic. Please prepare no more than five minutes of performance time/two poems. Sign up in advance by calling the Columbia Arts Center, or on the sign-in sheet when you arrive. The number for the Arts Center is 410-730-0075.

Light refreshments will be served. Books by both featured authors and open mic readers will be available for sale.

Poets Bruce Jacobs, Naomi Thiers and you.

Hosted by Linda Joy Burke.

April 9, 2019 • 7:00 p.m.

Columbia Association Arts Center

Bruce A. Jacobs is a poet, author, and musician. He has appeared on NPR, C-SPAN, and elsewhere. His two books of poems are Speaking Through My Skin (MSU Press), which won the Naomi Long Madgett Poetry Award, and Cathode Ray Blues (Tropos Press). His most recent nonfiction book is Race Manners for the 21st Century (Arcade/Skyhorse). His work has been published by dozens of literary journals and sites, including Beloit Poetry Journal, Gwarlingo, Truthout, and the 180 More anthology edited by U.S. Poet Laureate Billy Collins. He lives in Washington, DC.

Naomi Thiers grew up in California and Pittsburgh, but her chosen home is Washington-DC/ Northern Virginia. She is the author of three poetry collections: Only The Raw Hands Are Heaven(which won the Washington Writers Publishing House award), In Yolo County, and She Was a Cathedral(both from Finishing Line Press.) Her poems, fiction, and essays have been published in Virginia Quarterly Review, Poet Lore, Colorado Review, Grist, Sojourners, and other magazines and anthologies. Former poetry editor of Phoebe, she works as an editor for Educational Leadership magazine and lives in a condo on the banks of Four Mile Run in Arlington, Virginia.

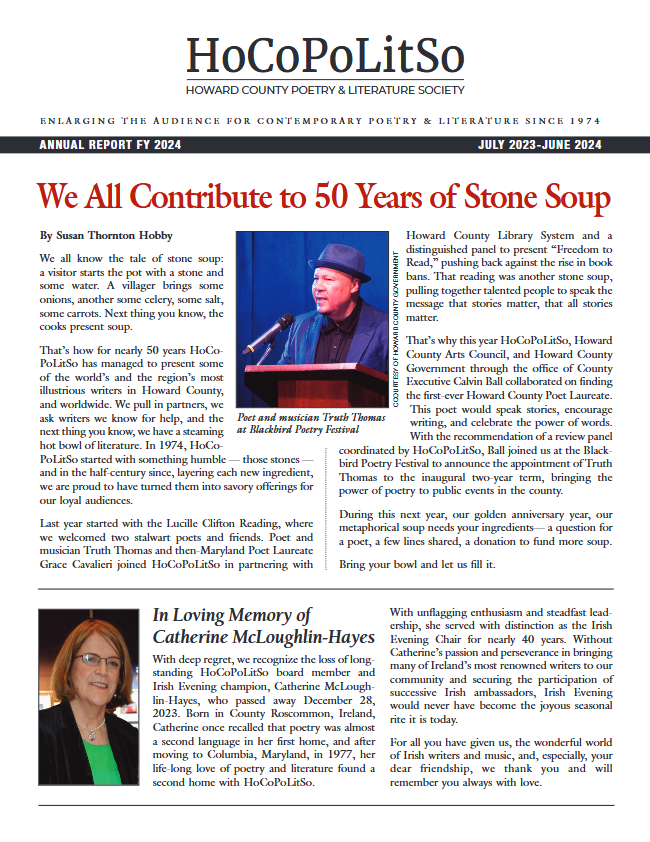

Remembering W.S. Merwin — Susan Thornton Hobby

W. S. Merwin, a fellow pacifist, writer, and gardener, was a hero in all things to me.

W. S. Merwin, a fellow pacifist, writer, and gardener, was a hero in all things to me.

The poet died this weekend at the age of 91 in his Hawaiian home. He was one of the first authors who wrote verse about the catastrophes of the Vietnam War and its effects not just on the American soldiers, but on the devastated Vietnamese countryside and people. He refused to accept his Pulitzer Prize for his book The Carrier of Ladders in 1971 because of the tragedies occurring in southeast Asia centering on the Vietnam War.

Merwin reclaimed his “garden,” nineteen acres of Hawaiian pineapple plantation land that had been wrecked by agricultural abuse. Over forty years, he hand-planted the dirt with 3,000 palm seedlings and transformed barren fields into a native rainforest. That land is now in permanent conservation.

But most of all, I admire Merwin for his gem-like poems of sheer beauty. What this writer could do with words – both his own and with those of French, Spanish, Latin and Italian poets that he translated – was astonishing.

Merwin visited HoCoPoLitSo in 1994, just after he had won the first Tanning Poetry Prize, which was awarded to a master American poet, but before he won his second Pulitzer in 2009. He spoke to a small group of 50 people about the craft of writing, then read his poetry to the audience that crowded the ballroom, lobby and stairways of Oakland Manor.

Earlier that day, he taped an episode of The Writing Life, HoCoPoLitSo’s writer-to-writer talk show. On that show, he spoke with poet Roland Flint about a coming environmental crisis in the world: “What is happening to the great forests in the world, I feel it like an illness,” Merwin said, thumping his fist into his belly. Because people have cut themselves off from the world outside their windows and screens, “we find ourselves in a place that is false and dangerous, and increasingly destructive.”

To watch him read his exquisite verse, “Late Spring,” “West Wall,” and “The Solstice” from The Rain in the Trees, and two poems from Travels, “Witness” and “Place” watch The Writing Life episode.

West Wall

W.S. Merwin

In the unmade light I can see the world

as the leaves brighten I see the air

the shadows melt and the apricots appear

now that the branches vanish I see the apricots

from a thousand trees ripening in the air

they are ripening in the sun along the west wall

apricots beyond number are ripening in the daylight

Whatever was there

I never saw those apricots swaying in the light

I might have stood in orchards forever

without beholding the day in the apricots

or knowing the ripeness of the lucid air

or touching the apricots in your skin

or tasting in your mouth the sun in the apricots

To learn more about Merwin and his life, watch the documentary about his life. Or visit the tribute page on his publisher’s site.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Recording Secretary

Poetry of Wit and Wonder — Eleventh Annual Blackbird Poetry Festival

Mississippi’s Poet Laureate Beth Ann Fennelly headlines the eleventh annual Blackbird Poetry Festival for HoCoPoLitSo. The festival, set for April 25, 2019, on the campus of Howard Community College, is a day devoted to verse, with workshops, book sales, readings, and patrols by the Poetry Police. The Sunbird poetry reading, featuring Ms. Fennelly, as well as poet Teri Cross Davis, local authors, and Howard Community College faculty and students, starts at 2:30 p.m. and is free. Ms. Fennelly will read from and discuss her poetry, including her most recent work, Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs, during the Nightbird Poetry Reading, starting at 7:30 p.m. in the Monteabaro Recital Hall of the Horowitz Center for Visual and Performing Arts. Nightbird admission tickets are $15 each (seniors and students $10) available on-line at https://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/4026338 or by sending a self-addressed envelope and check payable to HoCoPoLitSo, 10901 Little Patuxent Parkway, Horowitz Center 200, Columbia, MD 21044.

Fennelly’s newest book, Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs (2017), was selected as one of the ten best Southern books of 2017 by the Atlanta Journal Constitution. “Readers, you are in for a hootenanny of a wild ride. This is Fennelly at her most laid-bare, wickedly funny, and irrepressibly poetic best,” raves Kirkus Reviews. The director of the MFA program at the University of Mississippi, Fennelly has published her work in more than fifty anthologies and has won numerous awards and honors, including a Pushcart, the Wood Award from The Carolina Quarterly and The Black Warrior Review Contest. Fennelly is the author of three poetry collections: Open House (2002), Tender Hooks (2004), and Unmentionables (2008). She is also the author of a book of essays, Great with Child: Letters to a Young Mother (2006), “may be the best book ever to give for a baby shower” noted the Tampa Tribune. In 2013, Fennelly and her husband, Tom Franklin, co-authored a novel, The Tilted World, set during the 1927 flood of the Mississippi River.

Teri Ellen Cross Davis is the author of Haint, winner of the 2017 Ohioana Book Award for Poetry. A Cave Canem fellow serving on the advisory council of Split This Rock, Davis is the poetry coordinator for the Folger Shakespeare Library. Reviewing Haint, The Triangle’s Sam Sweigert wrote, “Beginning to end, Cross Davis beckons her readers to shine a light and to witness the slow magic of a soul’s journey through life’s knowings and unknowings.”

Steven Leyva, a Cave Canem fellow and author of the chapbook Low Parish, will offer a workshop on “The Poetics of Animé” as part of the festival. Leyva, who is an assistant professor at the University of Baltimore, will hold his free workshop at 9:30 a.m. in the Rouse Company Foundation Student Services Hall, room 400.

Poetry Out Loud State Champions pose for a photo at the State Finals. Hanna Al-Kowsi, Marriotts Ridge High School, Howard County (second place winner) is standing on the right. Photo credit: Edwin Remsberg.

Hanna Al-Kowsi, of Marriotts Ridge High School, will perform her winning poetry recitation at the Nightbird. Hanna won first place in the regional tri-county and second place in the state-wide Maryland Poetry Out Loud competition that recognizes great poetry through memorization and performance.

For more than 40 years, HoCoPoLitSo has nurtured a love and respect for the diversity of contemporary literary arts in Howard County. The society sponsors literary readings and writers-in-residence outreach programs, produces The Writing Life (a writer-to-writer talk show), and partners with other cultural arts organizations to support the arts in Howard County, Maryland. For more information, visit www.hocopolitso.org.

HoCoPoLitSo receives funding from the Maryland State Arts Council, an agency funded by the state of Maryland and the National Endowment for the Arts; Howard County Arts Council through a grant from Howard County government; The Columbia Film Society; Community Foundation of Howard County; and individual contributors.

Give that poet a laurel wreath -To go with her leather jacket

Poetry scares people.

Poets Laureate? That sounds like they should be wearing circles of laurel leaves on their heads and reciting from hilltops. Super scary.

The new Maryland Poet Laureate is the opposite of that image, though I would highly condone granting her a laurel leaf crown. Grace Cavalieri is more poetry’s grandma, albeit one who wears a leather motorcycle jacket and writes collections of poetry about Anna Nicole Smith.

“She is not a gatekeeper, but one who opens the gate and says, ‘Come in, you are welcome here,’ ” said poet Teri Ellen Cross Davis, head of the Poet Laureate Selection Committee, who introduced Cavalieri on the last day of February at her induction party in Annapolis. (And will offer a workshop and read with Beth Ann Fennelly at this year’s Blackbird Poetry Festival.)

After Davis and other dignitaries finished praising her, Cavalieri beamed at the audience, including her four daughters sitting in the front row. She explained that at their family home, “Poetry has always sat at the table.”

For more than forty years, Cavalieri has hosted “The Poet and the Poem,” an interview show on public radio, now carried by the Library of Congress. She’s written more than 20 books and chapbooks of poetry, had 26 plays produced on the American stage, and won honors like the Pen-Fiction Award, the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Award, and the inaugural Columbia Merit Award from Folger Shakespeare Library.

Those awards sound off-putting, but Grace’s speech to the gathered crowd of past Maryland Poets Laureate, friends, former students at Columbia’s 1960s experimental Antioch College, fellow poets, and Italian cousins wasn’t.

“Here’s what poetry does. It slows us down,” Cavalieri said. “Poetry is a shelter, a haven, it’s dreaming on a page. Poetry keeps us from being lonely. It’s a bridge. It makes us more human.”

For young people, whom Cavalieri hopes most of all to reach with her message, poetry finds chinks in their armor, the defenses they’ve built up to navigate the world.

For young people, whom Cavalieri hopes most of all to reach with her message, poetry finds chinks in their armor, the defenses they’ve built up to navigate the world.

“Through writing, they find out who they are. Poetry is self-discovery. You find out where you’ve been and where you’re going,” she said. “I didn’t know who I was until I was 80, now I’m enjoying it very much.”

And after the laughter and applause died down, Cavalieri read one of her signature poems, about her grandparents’ Italian restaurant in Trenton, NJ. The poem’s topic? Something everyone loves – besides Grace – pizza.

Cavalieri came to HoCoPoLitSo’s very first event, on Nov. 19, 1974, with poets Carolyn Kizer and Lucille Clifton. And she started reading her work and teaching workshops with us in 1980, and was our poet-in-residence to the county schools in the 2002 to 2003 academic year. The students and teachers loved her for her energy and enthusiasm, which has not flagged a bit since then.

Cavalieri hasn’t stopped writing because she has this new laurel. Here’s her latest poem, about her latest job:

Terms of Office

for Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr. January 16, 2019

May our Governor hear the language of the people

as terms of his office.

“Language” simply means many people

Have come together to make words.

There are nearly 100,000 words in the English language

I’ve chosen exactly 246, but I want to shine them up

To speak about a man serving in high office;

A man who will walk by the beautiful waters

Of our bays, rivers, rivulets;

One who continues with inner strength

Clearing new paths with elasticity for every kind among us—

Who knows love and hope are not holiday greetings

But governing principles—

A man aspirational for humanity.

Language always leads us to the soul of each matter,

And today it rinses words clean, renewing meaning:

Independence of thought

An honorable nature

Clear vision

Calm in the eye of national storms.

From the rich bottom lands of southern Maryland

To the forested hills of our western state—

From the dynamic energy of northern Maryland

To his own hometown—

May our Governor’s inner spirit seek compassion before action,

May his wisdom see that the heart’s choice dictates the mind’s decisions,

May he be rewarded with radiant pride for his integrity.

In speaking of success, Ralph Waldo Emerson said:

“Each one has an aptitude to do easily some feat impossible to any other

And to do otherwise undermines the talents of all others.”

May Governor Hogan be rewarded with radiant pride for his integrity.

Grace Cavalieri

Maryland Poet Laureate

Susan Thornton Hobby

HoCoPoLitSo recording secretary

An Inconvenient Book Club – Start Reading!

Register online or by calling 410-313-1950.

————-

Susan Thornton Hobby

Recording secretary

Make Poetry Great Again (Though It Was Always Great)

Irish Ambassador to the United States Daniel Mulhall. Photo by Douglas Graham.

His Excellency Daniel Mulhall, the Irish Ambassador to America, drew a hearty laugh from the audience at Friday night’s Irish Evening of Music and Poetry.

As a daily counterbalance to the insanity on Twitter, Mulhall sends out a few lines of Irish poetry every morning.

To the audience at the poetry reading last week, Mulhall joked that he’s starting a campaign: “It’s time to Make Poetry Great Again.”

After the laughter died down, HoCoPoLitSo board members could be heard muttering amongst themselves, “Poetry was always great.”

But timeline quibbles aside, HoCoPoLitSo was thrilled to welcome the ambassador and sterling poet Vona Groarke to the forty-first Irish Evening.

Last Friday morning, in tribute to Irish Evening, Mulhall sent into the Twitterverse a few lines from Groarke’s beautiful poetry:

Anyway, the leaves were almost on the turn

And the roses, such as they were, had gone too far.

It was snow in summer. It was love in a mist.

It was what do you call it, and what is its name

And how does it go when it comes to be gone?

There’s at least one thing that Mulhall and U.S. President Donald Trump share – they like to start the day with a Tweet. But oh, there’s a world of difference between them.

The poems Groarke read on Friday night were both tender and fierce. Her “Pier,” was well applauded for its verve in chronicling the leap from a pier into the Atlantic on Spittel beach, on the West coast of Ireland. Though Groarke confessed that she hasn’t yet made the leap herself, she’s watched it done, she said, a bit sheepishly. And the poem proves she can feel it.

Vona Groarke. Photo by Douglas Graham.

Many in the audience commended Groarke’s translation from the Irish – the first by a woman poet – of “The Lament for Art O’Leary.” This poem chronicles the mourning and protest of a wife, keening over the body of her Catholic husband, killed by the Protestants, ostensibly for having too fine a horse. And Groarke’s translation was both sensual and sorrowful.

The selections of prose Groarke read from Four Sides Full, her book of prose about art frames, were illuminating, particularly the anecdote about the show of empty frames in the Hermitage in Leningrad, signifying the hiding of artwork to preserve it.

Poetry and music brought some 300 people together last Friday night. Perhaps verse can heal divisions in countries, between people, if we only open our hearts to others’ stories.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Recording secretary

book clubs: who, what, and why

By Laura Yoo

Here’s a small sample of the books my book club has read. I also listened to the following audio books: Hillbilly Elegy by J. D. Vance, Born a Crime by Trevor Noah, The Book of Joy by Dalai Lama and Desmond Tutu.

A popular image of book clubs is that it’s an “excuse” for women to get together to drink wine. Of course, there is nothing wrong with that. But my book club, which I joined two years ago, is actually a book club. The 14 member group is super organized, and we actually read the books that we choose as a group (done very democratically). There is wine and a good amount of talking politics, but overall it is a reading club. There is always robust literary discourse.

Book clubs and the battle of the sexes

Pew Research reports that 11% of Americans are involved in some kind of a reading circle or a book club. But in general book clubs are seen as something women do. Men have poker nights. Women have book clubs.

It turns out that it actually has a historical beginning as a female activity. Audra Otto, writing for MinnPost, reports 1634 as the first known instance of an organized reading group in (or on the way to) America:

On a ship headed for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, religious renegade Anne Hutchinson organizes a female discussion group to examine sermons given at weekly services. Eventually condemned by the Bay Colony’s general assembly, the gatherings inaugurated a tradition of women’s analytical discussion of serious texts.

The banning of this organization signals that a gathering of women to share ideas was seen as dangerous or maybe even evil. But, women continued to organize elsewhere. Hannah Adams formed a reading circle in the late 1760s and Hannah Mathers Crocker in 1778. Adams’ and Crocker’s reading circles are revolutionary in that they created opportunities for women to form communities of intellectual development when women couldn’t go to school or college.

Another example of such revolutionary gatherings is the Friends in Council formed by Sarah Atwater Denman, the oldest continuous women’s literary club in America.

In November of 1866, Denman invited 11 ladies to her home to create a study plan. She wanted each member of her book club to develop a philosophical point of view for herself, and a study plan was an excellent place to begin. Over time, Friends in Council consumed great works of history and philosophy, spending two years on Plato alone.

So, historically speaking, the book club has been a female act of subversion.

Book clubs in the 21st century

A 2016 The New York Times article caused some stir when it profiled The Man Book Club, the International Ultra Manly Book Club, and the NYC Gay Guys’ Book Club. The article mentioned that the The Man Book Club in California has a “No books by women about women” rule. This and other details about these men’s book clubs suggested chauvinism and sexism. The backlash was so strong that The Man Book Club issued An Apologia on their website, in which they explain how they arrived at their group name (think the Man Booker Prize) and how they select their books (which does include books by women). It seems that because book clubs are pegged as “female” activity, these men hyper-emphasize the “man” part of their book club. While many criticized these men clubs, others like Slate’s L.V. Anderson came to their defense, saying,

We shouldn’t see all-male book clubs as a reactionary backlash against female book clubs, or an attempt to co-opt a traditionally female space, but as a way for men to enjoy the social and intellectual benefits of book clubs without destroying the homosocial camaraderie of all-female book clubs.

Today, book clubs go beyond groups of friends getting together to read and chat. Websites like Meetup.com and other social media tools help us organize or join groups with strangers. The NYC Gay Guy’s Book Club, for instance, has 120 members on Meetup.com and anywhere between 10 to 60 members show up for a meeting at a public library. The search results for book clubs in my area include The Girly Book Club of Baltimore, Intersectional LGBTQ+ Allies Book Club for Women of DMV, and the Silent Reading Club (of Rockville). I am particularly loving this idea of gathering in a group to read silently.

Recently, I was invited to attend another friend’s book club gathering to talk about Michelle Obama’s memoir, Becoming. This was a much smaller group – there were only four of us that night. We got comfy on the couch, drank wine, talked about the book a little, then talked mostly about our families, our kids, education and schools, about how we grew up, and even some politics. It was a lovely evening.

Book clubs are not about the books (only)

I think we can see that the book club is not always (only) about books. For many, the book club is a way to see friends and form meaningful bonds, as both the Man Book Club and the International Ultra Manly Book Club report. For others, the book club is a way to meet new people. As Jon Tomlinson, founder of the NYC Gay Guys’ Book Club says, “People come to connect, to find their place in a new city, to fall in love.”

For Scarlett Cayford, the book club was a way to meet people when she moved to London – four years later, she was still going to the same book club. As Cayford says, book clubs are not about books – they are “about bonding, and they’re about conversation, and they’re about sharing secrets. I can’t speak for all, of course, but the book clubs I‘ve attended usually end up involving about 30 minutes of intense book discussion […] and nigh on three hours on the subject of different sexual proclivities.”

Well, my book club does not discuss sexual proclivities. Nonetheless, I look forward to my monthly book club gatherings for two reasons. First is that I have time built into my schedule to see my friends. We take turns hosting at our homes and facilitating the discussion. I enjoy the company of these women who are my colleagues, mentors, and friends – and I cherish the opportunities to see them regularly.

The second is that the book club makes me read. Sometimes – like my students – I cram my reading just a few days before the gathering. Recently, I’ve had to admit to myself that I watch more than I read. I’m much more likely to pick up my tablet or turn the TV on to binge-watch something deliciously useless. After a long day at work and shuttling the kids around, it’s a relief to change into pajamas and cozy up in my “reading chair” to watch the outrageously handsome Hyun Bin in a Korean drama or ass-kicking Keri Russell in The Americans. I used to actually read in that reading chair. After a long day at work and shuttling kids around, it was a relief to get lost in a good book. But the ease of accessing television shows on mobile devices is oh-so-tempting. So, my book club is my antidote to binge-watching.

Nerd-by-Nerd

This month, our book club is reading Word by Word by Kory Stamper. I am not sure what my book club members are feeling about it – we haven’t met yet – but I am loving every page of this book. I am a word-nerd, and I am savoring the juicy details of how the dictionary is written and how we may be in the middle of a seismic shift in the meaning of “of” (as suggested by the newfangled phrase “bored of” as opposed to “bored from” and “bored with”). I’m giddy about exchanging tweets with Stamper about her use of the word “goddamned” which I found amusing. I’m enjoying the book, for sure. But I’m REALLY going to enjoy talking about it with my friends this week.

I don’t know about subversion and rebellion and all that, but I know I enjoy the company of my friends, books, and wine – that’s a powerful combination.

Save the Date! HoCoPoLitSo is sponsoring a book club of cli-fi, climate fiction, at the Miller Library, one book each season. The first book, Margaret Atwood’s The Year of the Flood, will be discussed April 4, 7 to 8 p.m. Discussion will be led by Susan Thornton Hobby, a consultant to HoCoPoLitSo, and Julie Dunlap, a writer and environmental educator. More details to come!

On Reading: Two Love Poems by Vona Groarke and It’s Time To Fall In Love With Irish Evening

I swoon at a good love poem. Here’s a quick introduction to two that have me dizzy on my feet.

Vona Groarke Photograph: Ed Swinden/The Gallery Press.

Both are by Vona Groarke, HoCoPoLitSo’s guest for this year’s evening of Irish writing and music – it’s this Friday, don’t just mark your calendar, get your ticket. I offer these poems here as foreshadowing for the event, a beloved favorite annual occurrence that’s been going on for more than forty years now. Both poems I discovered while reading up in advance of her visit. Each has me in its own way a little breathless, smitten, staring newly in love at their marvel.

“What leaves us trembling…”

“Shale” is just a great little love poem, I think. It left me trembling. Read the the length of the poem here, it’s not long, but I am only sharing a few stanzas in this piece. It starts and ends by a ‘not telling’ device, meanders nicely in-between, but what it ends up saying along the way.

What leaves us trembling in an empty house

is not the moon, my moon-eyed lover.

Say instead there was no moon

though for nine nights we stood

on the brow of the hill at midnight

and saw nothing that was not

contained in darkness, in the pier light,

our hands, and our lost house.

I described it to a friend as perhaps opaque while trying to be translucent, but opalescent all the while. It’s that opalescent surface that’s dazzling and intriguing, then you peer through the shimmer into what the poem’s lovers share as example of us all. There’s the narrator relating a contemplative monologue, a scenario that is part plot, part seeming. I am not sure what is actually moment and what is shared mind, but it doesn’t matter, the poem’s lovers seem to find themselves at that point of realization and action that comes when two bodies/souls make that moment out of circumstance and each other that is a fusing. And that ending, wow, an unsayable understanding just left there. You know what I’m saying?

The sea is breaking and unbreaking on the pier.

You and I are making love

in the lighthouse-keeper’s house,

my moon-eyed, dark-eyed, fire-eyed lover.

What leaves us trembling in an empty room

is not the swell of darkness in our hands,

or the necklace of shale I made for you

that has grown warm between us.

That warming of such a tangible object is quite a making. What a poem. I’ll go back and read it again and again, wanting that answer, finding that stone.

“Let the worst I ever do to you be die.”

An aubade is a first-thing-in-the-morning poem lovers share to each other. Think of the nightingale and the lark in Romeo and Juliet. In that case, the debate was about which bird’s song was determining the moment over, the day begun, and the time together over, or not, one being the voice of morning, the other of night. A clever quartet for the two still in bed.

The poem “Aubade” from Spindthrift takes on a different sort of in-between-lovers morning scenario. As readers, we are on the sickbed where the caretaker of the couple narrates understanding and affection while tending the beloved. It is hardly a place for a love poem, one would think, but oh how it is. The poem is pictured here in its entirety, so have read.

It’s a way more transparent read that the previous piece, but you do gain a sense of Ms. Groarke’s way of presenting the world through her observations and language. Transparent, but the glass is beautifully etched with fern and foam.

And there’s one line that just dropped me:

Let the worst I ever do to you be die.

Such a sober realization of the inevitable, that we will die on those we love and that is quite a thing should we be the first to go. There’s a dearness and commitment in that line that is quite a realization. Ideally, it is the worst we’ll do. Is love ever ideal? And then that last, true-love line, pure presence, able and ideal, and love in action.

I am here, blessed, capable of more.

Beautiful. Love poems aren’t just for the young, the beautiful, the wooing. They are for the lifelong and every moment.

It’s time for you to fall in love… with Irish Evening.

Mentioned above, Vona Groarke will be reading from her work followed by a concert of Irish music and championship step-dancing at HoCoPoLitSo’s 41st Irish Evening on Friday, February 8, 2019 at Smith Theatre in the Horowitz Center for Visual Performing Arts on the campus of Howard Community College in Columbia, Maryland.

Mentioned above, Vona Groarke will be reading from her work followed by a concert of Irish music and championship step-dancing at HoCoPoLitSo’s 41st Irish Evening on Friday, February 8, 2019 at Smith Theatre in the Horowitz Center for Visual Performing Arts on the campus of Howard Community College in Columbia, Maryland.

For this year’s Irish Evening, music will be performed by The Hedge Band, featuring Laura Byrne on flute, NEA National Heritage Fellowship winner Billy McComiskey on box accordion, Donna Long on piano, and Jim Eagan on fiddle. Traditional Irish Dancing will be performed by Teelin Irish Dance, featuring owner and director Maureen Berry and the 2016 World Champion Saoirse DeBoy.

It’s going to be a special evening. You are going to fall in love with Irish Evening.

The program begins at 7:30 p.m. Click here for tickets.

Tim Singleton

Board Co-chair

“He has these great books that give me feelings,” a young reader raves about Jason Reynolds

When young adult bestselling author Jason Reynolds heard that HoCoPoLitSo’s archive of The Writing Life shows featured episodes with Amiri Baraka and Lucille Clifton, he shook his head in wonder. When he heard that HoCoPoLitSo’s web site had more than one hundred taped shows with literature’s rock stars, he said, “Oh, I’m going down that rabbit hole!”

When young adult bestselling author Jason Reynolds heard that HoCoPoLitSo’s archive of The Writing Life shows featured episodes with Amiri Baraka and Lucille Clifton, he shook his head in wonder. When he heard that HoCoPoLitSo’s web site had more than one hundred taped shows with literature’s rock stars, he said, “Oh, I’m going down that rabbit hole!”

And indeed, YouTube has offered scholars, readers, and writers an amazing opportunity – to learn about craft from contemporary literature’s greatest writers. Since 1985, HoCoPoLitSo has been preserving on video a series of half-hour conversations between diverse authors. Many of those writers have recently gone to afterlife rooms of one’s own: Baraka, Clifton, Richard Wilbur, Donald Hall, Gwendolyn Brooks, Frank McCourt.

No one has to set their DVR to catch the cable replays of these shows – just log onto YouTube.com/hocopolitso anytime. HoCoPoLitSo has spent more than ten years digitizing the brittle and fragile archival tapes to preserve those shows. The YouTube channel has garnered more than 1,100 subscribers and 400,000 views. And our latest upload, the show recorded with young adult author and poet Laura Shovan speaking with Reynolds, is already gathering raves.

One school administrator, after watching the show with Jason Reynolds, wrote, “This is a great conversation about author’s craft and decisions in a book (Long Way Down) that many of our students have read! Sharing with all my teachers.”

And a student reader wrote: “My language arts teacher met him a year ago and he signed two books for her and my teacher always pointed out the heart he put in the book and she always brags and says that this is going to be our favorite author and so far yes, he has these great books that give me feelings and before the Spider Man book came out, my teacher knew too.”

Reynolds is converting readers, just like HoCoPoLitSo wants to do.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Executive producer of The Writing Life