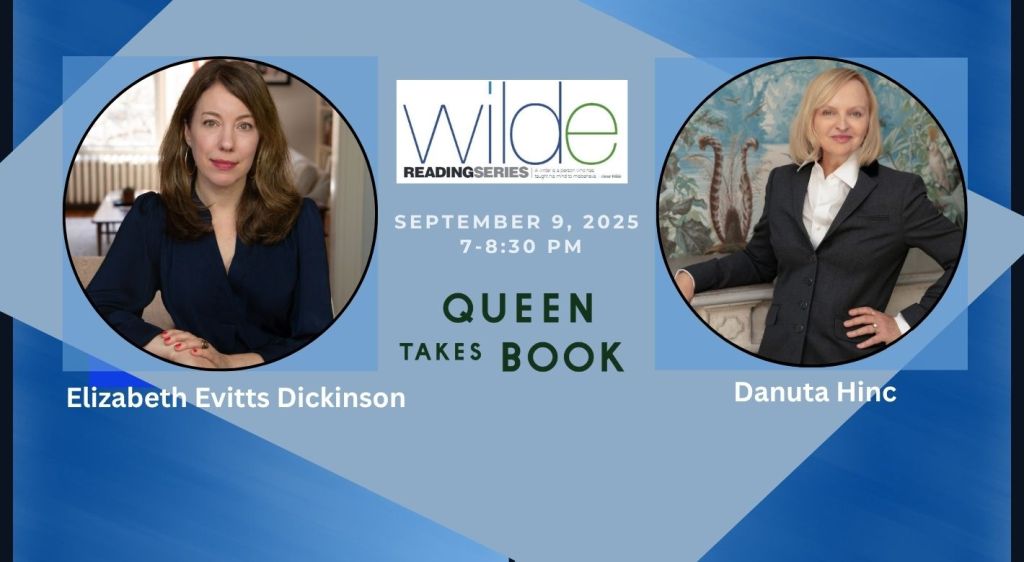

HoCoPoLitSo welcomes all to the September edition of the Wilde Reading Series, which this year proudly opens its tenth season of highlighting local authors in Howard County. This month’s reading features Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson and Danuta Hinc, hosted by Ann Bracken. Please join us at independent bookstore Queen Takes Book on Tuesday, September 9th at 7 p.m., at 6955 Oakland Mills Rd, Suite E, Columbia MD, 21045. Please spread the word— bring your friends, family and students! Light refreshments will be served and books by the readers available for sale.

An open mic follows the featured authors and we encourage you to participate. Please prepare no more than five minutes of performance time, about two poems, and sign up when you arrive.

Below, get to know Elizabeth and Danuta!

Who is the person in your life (past or present) that shows up most often in your writing?

Elizabeth: My grandmother. She died in a tragic way in the 1960s before I was born, and it was a family secret for decades. I’ve long understood that her death had a ripple effect on me and my family, and I’ve written several essays about her in an effort to understand who she was and what happened.

Danuta: In When We Were Twins, the figure who returns again and again is my mother. Her story of delivering my twin sisters, Hanna and Mariola—who were born three years before me and who lived for only ten days—was one of those family narratives I carried with me from childhood, though it was often wrapped in silence. That brief and fragile life, and the way my mother bore it, became the quiet undertow of the novel, in Taher’s mother, Laila. Writing it, I felt as though I was reaching toward a presence I had never truly known, yet one that shaped me profoundly. The sisters who were absent and yet always there, their absence rippling through my mother’s body, her memory, and my own beginnings.In my novel-in-progress, Sisters, the circle widens. Here it is not only my mother’s voice but my whole family that steps into the light—my parents, my grandparents, and most of all, my sister, Olka, Aleksandra. She was my constant companion and, in many ways, my first co-creator of stories. We grew up together in Poland at a time of political tension and silence, but our own bond was full of invention, curiosity, and defiance. When I write about her, I feel I am also writing about that primal closeness between siblings, the way we are each other’s mirrors, rivals, guardians, and witnesses. In Olka, and in the family who shaped both of us, I find the wellspring of the questions that drive my work, how memory is carried, how history lives in the body, and how love binds us through even the most difficult silences.

Where is your favorite place to write?

Elizabeth: I need quiet when I write. I can’t get anything done in a busy cafe, for instance, because I’m easily distracted and I absorb the energy around me. I write in my home office mostly. But my all-time favorite place to write is when I take myself to my favorite state park in Western Maryland and I get to write in the cabins there in front of a crackling wood stove surrounded by nature.

Danuta: I have two places that anchor me when it comes to writing. One is my home in the suburbs of Annapolis, where the familiar rhythm of the seasons and the quiet order of daily life give me steadiness. The other is our condo on the beach in Ocean City, Maryland, where the horizon of water and sky seems to stretch language itself, reminding me of the vastness that stories can hold. These are the places where I return, where the work continues steadily.

And yet, over the years, I have learned that what inspires me most deeply is not the familiar but the unsettled—the act of moving, of inhabiting new spaces that are not quite mine. Being in a new place shakes me open. It makes me notice differently, listen more closely, and enter into a kind of heightened attention that is essential for writing. Most recently, it was Africa, where we spent the month of June traveling along the West Coast, visiting nine countries. Each day offered a new cadence, a new rhythm, a new way of seeing. Before that it was Indonesia and Australia, where we spent a month in 2023, and earlier still, the Mediterranean, where we spent three weeks surrounded by a history layered with myth.

I always carry notebooks with me when I travel. Sometimes the notes are directly about the landscapes and encounters I experience, but often they begin to circle back to the novel I am working on at the time. What I discover is that travel doesn’t take me away from my writing—it folds into it, expands it. Movement, displacement, and the encounter with elsewhere always return me to the deeper questions I am exploring in fiction–memory, belonging, silence, and the way stories migrate across borders and time.

Do you have any consistent pre-writing rituals?

Elizabeth: I tend to set the stage by clearing my desk and lighting an unscented candle. I’ll have water and coffee or tea. And I’ll sometimes play what I think of as “transition music” to get me grounded, usually music by Stan Getz or Erik Satie or François Couperin. But when I write, I need silence.

Danuta: Reading has always been my most faithful ritual. Before I write, I read—not necessarily books directly related to what I am working on, but words that remind me of what language can do. A poem, a page of philosophy, a fragment of fiction, they open the door, set my mind into motion, remind me that writing is part of a long conversation that stretches across centuries. Reading is the way I tune my instrument before I begin to play.

Another ritual, though less deliberate, is not eating. I think most clearly when I am slightly hungry, when the body is alert rather than satisfied. The clarity of thought, the sharpness of images, the way ideas connect to one another, these come most vividly to me in that state of attentiveness. Over time, I even changed my diet to keep my brain sharp, learning how profoundly the body influences the mind.

In some ways, these rituals are small acts of silence and restraint—reading before speaking, withholding before consuming. They echo the themes that shape my work, listening before telling, holding absence before filling it. Writing asks for that kind of pause, the interval in which something unspoken can rise to the surface.

Who always gets a first read?

Elizabeth: I don’t have a standard first reader. It depends on the project. Sometimes it’s the editor I’m working with. Sometimes it’s a fellow writer who I trust. Because I write journalism, essay, memoir, short fiction, and longform nonfiction books, I tend to switch up who reads my work first.

Danuta: My husband, Tim, is always the first reader. He is, quite simply, a superb gift to my writing. His honesty is unwavering. He never avoids the difficult or probing question, never offers easy praise in place of real engagement. What he gives me instead is insight, the kind that comes from reading deeply, from taking literature apart with the precision of someone who studies and teaches it, even though his profession is engineering. He reads with rigor, with clarity, and with a sensitivity that pushes me to see the work more fully than I could on my own.

The next reader is my son, Alex, whose relationship with books astonishes me. He is thirty years younger than I am, and yet I sometimes think he has already read more than I ever will. His reading is wide, sophisticated, and fearless. He discusses literature on a level that both humbles and inspires me, and his way of seeing connections—between texts, between ideas, between worlds—reminds me that literature itself is an endless conversation.

To place a manuscript in their hands is both terrifying and consoling. Terrifying because I know they will see the work without illusions, and consoling because their vision is what steadies mine. Writing is solitary, but in these first readings, I find the essential witness, someone to hold the silence with me, and then break it with truth.

What is a book you’ve read more than twice (and would read again)?

Elizabeth: So many! But I’ll pick two: Pilgrim at Tinker Creek by Annie Dillard and One Man’s Meat by E.B. White.

Danuta: I rarely read books more than once. There are simply too many waiting for me, and time feels far too short. When I read a book I love, I often tell myself I will return to it, but almost always I move forward instead, following the long line of unread voices that call.

What I do find myself doing, however, is reading a book in Polish, and then again in English translation. Perhaps that counts as reading it twice. But what interests me most in that repetition is not the comfort of familiarity, but the difference—the way language transforms the same thought, the same image, into something subtly or even profoundly new. Translation fascinates me, how one text flows into another like water through a different channel, carrying with it both what remains and what shifts.

This preoccupation has followed me into my novel-in-progress, Sisters. In Part V, I imagine a correspondence between Saint Paul and Saint Thomas, letters that never existed but that I invent. Writing them has drawn me back to the Bible and the ways it has moved across languages: Aramaic, Hebrew, Greek, Latin, English, Polish. Each translation both preserves and alters, both reveals and conceals. It is this paradox—the possibility that words can both endure and transform—that keeps me thinking about language itself as the great unfinished text, one that none of us can ever read just once.

What is the most memorable reading you have attended?

Elizabeth: I saw the poet Rita Dove speak at the University of Buffalo in the 1990s and she was transcendent.

Danuta: There have been too many to name, but a few rise instantly to the surface. The first was hearing Czesław Miłosz read at the Library of Congress in the 1990s. For me, it was like stepping across an invisible border. In high school and college in Poland, his work had been banned, his voice officially silenced by the communist government. To sit in Washington, D.C., a decade later, and listen to him read his own words aloud—it felt like touching something sacred, as though history itself had shifted and allowed what had once been forbidden to return in the most direct and human form.

Another unforgettable moment was a conversation between Seamus Heaney and Derek Walcott. Listening to them, I felt an overwhelming sense of intimacy with greatness. It wasn’t only their poetry that moved me, but the generosity of their presence, the way they spoke to one another as peers and friends. I fell in love with both of them in that conversation, their voices, their wisdom, their humanity.

And then, more recently, Olga Tokarczuk at Politics and Prose in Washington, D.C., just a year before she received the Nobel Prize in Literature. I was impressed not only by her luminous intelligence, but also by her translator, Jennifer Croft, whose voice carried the work across languages with such care and brilliance. That evening reminded me again how literature is never a solitary act, but a dialogue, a movement between writer and reader, author and translator, silence and speech.

• Elizabeth Evitts Dickinson is the author of the critically-acclaimed book Claire McCardell: The Designer Who Set Women Free, which came out in June from Simon & Schuster. Named a New York Times Editors’ Choice, an Amazon Editor’s pick for Best History, and a must-read book featured in Oprah Daily, The Atlantic, Elle, Forbes, Harper’s Bazaar, and on NPR’s All Things Considered, among many others, the book has been hailed as an exceptional biography and an essential read that “puts the American fashion icon Claire McCardell back in the pantheon,” according to The New York Times Book Review.

Elizabeth can be found online at eedickinson.com, and on Instagram @elizabethevittsdickinson.

• Danuta Hinc is a Polish American novelist and essayist, author of When We Were Twins, praised by Kirkus Reviews as “a subtle psychological snapshot of radicalization.” Her work has appeared in Literary Hub, Washingtonian, Popula, and Consequence Magazine. She holds an M.A. from the University of Gdańsk and an M.F.A. from Bennington College. A recipient of the Barry Hannah Merit Scholarship, she is a Principal Lecturer in English at the University of Maryland.

Danuta’s online presence includes danutahinc.com, danuta.substack.com, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn.