Author Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah to Deliver Keynote at Howard Community College’s Inaugural Bauder Lecture

Acclaimed author of “Friday Black” will be joined in conversation with local author Tope Folarin

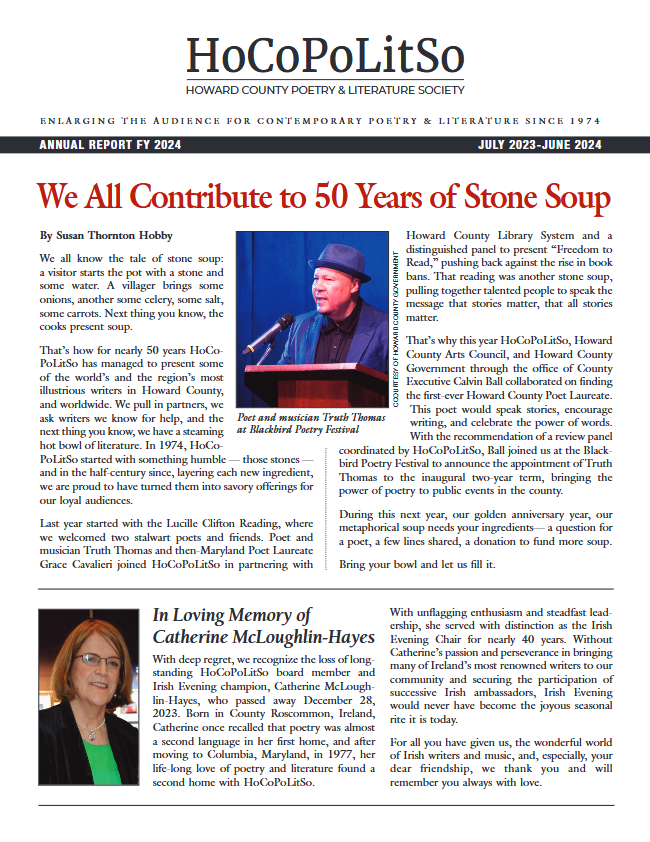

COLUMBIA, MD – Howard Community College announced that Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, the New York Times-bestselling author of “Friday Black,” will deliver the keynote at the inaugural Bauder Lecture. Adjei-Brenyah will participate in the virtual event on March 4, 2021, at 12 p.m., which also will include a conversation with Washington, DC-based writer Tope Folarin.

Adjei-Brenyah’s debut work, “Friday Black,” is a collection of twelve short stories that explore the injustices experienced by Black men and women in the U.S. Adjei-Brenyah, a professor at Syracuse University, uses fiction, humor, and shock to tackle urgent instances of racism and cultural unrest in America.

His work has appeared or is forthcoming from numerous publications, including the New York Times Book Review, Esquire, Literary Hub, the Paris Review, Guernica, and Longreads. He was selected by Colson Whitehead as one of the National Book Foundation’s “5 Under 35” honorees, is the winner of the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award and the William Saroyan International Prize, and a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle’s John Leonard Award for Best First Book, the Dylan Thomas Prize and the Aspen Words Literary Prize.

Following his keynote, Adjei-Brenyah will be joined by Tope Folarin, a Nigerian-American writer based in Washington, D.C., and the author of “A Particular Kind of Black Man,” for an in-depth conversation. Folarin won the 2013 Caine Prize for African Writing, was recently named a “writer to watch” by the New York Times, and was recognized among the most promising African writers under 40 by the Hay Festival’s Africa39 initiative.

The Bauder Lecture by Howard Community College is made possible by a generous grant from Dr. Lillian Bauder, a community leader and Columbia resident. Howard Community College will present an annual endowed author lecture known as The Bauder Lecture, and the chosen book will be celebrated with two student awards. Known as the Don Bauder Awards, any Howard Community College student who has read the featured book is eligible to respond and reflect on the book in an essay or other creative format. The awards honor the memory of Mr. Don Bauder, late husband of Dr. Lillian Bauder and a champion of civil rights and social justice causes.

“Friday Black” was selected by the Howard County Book Connection committee as its choice for the 2020–2021 academic year. The Howard County Book Connection is a partnership of Howard Community College and the Howard County Poetry and Literature Society.

To learn more about the Bauder Lecture and RSVP for the event, visit howardcc.edu/bauderlecture.

For more information on Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, “Friday Black,” and the Howard County Book Connection, visit https://howardcc.libguides.com/bookconnection2020.

Behind the Scenes of the Poetry Moment Series

We’ve all been swirling around in the frenetic cloud of crazy that has been the last twelve months. For HoCoPoLitSo, one thing has settled out of the hubbub. Poetry is something that helps. Hearing poetry, reading verse, listening to another soul speak truth is a balm.

National Poet Laureate Joy Harjo explains it well.

“When I began to listen to poetry, it’s when I began to listen to the stones, and I began to listen to what the clouds had to say, and I began to listen to other. And I think, most importantly for all of us, then you begin to learn to listen to the soul, the soul of yourself in here, which is also the soul of everyone else.”

If there’s any time we need to listen to our souls, and to the souls of other folk, it’s now.

The Poetry Moment series was created as a response both to the pandemic and to the Black Lives Matter movement. Since 1974, HoCoPoLitSo has been deliberate in its inclusion of authors to represent the fullest range of human experience. We have long believed that opening a book, reading a poem, or attending a literary event can be a powerful humanistic journey of exploration, education, and enlightenment.

The project evolved from a broad-based poetry video series to focus for the first eleven weeks on amplifying the voices of Black poets who have visited our audiences. Later, we added the voices of poets of different backgrounds.

And in November, we started videotaping young actors from Howard Community College’s Arts Collective reading introductions to the archival video of poets and their work. Directed by Arts Collective’s Sue Kramer, these actors–Chania Hudson, Sarah Luckadoo, and Shawn Sebastian Naar–spent many Monday evenings learning about poetry, tripping over tricky names, and recording video introductions that help explain the poems to viewers. They handled their own styling, and even set up their own lighting and sets.

I asked the actors a few questions about the project and its evolution, and loved their responses. Naar, who portrayed Langston Hughes for HoCoPoLitSo’s 2019 Harlem Renaissance Speakeasy, has taken on roles for Spotlighter’s, Wooly Mammoth, Howard University, and the Kennedy Center. Hudson, who was the Harlem Renaissance Gwendolyn Bennett, is receiving her bachelor in fine arts from UMBC this spring in theater, and has played in many Arts Collective shows, as well as performances at UMBC and Rep Stage. Sarah Luckadoo is an actor, choreographer, movement coach, and teaching artist who has worked with the equity company Ozark Actors Theatre in Missouri, Red Branch Theatre Co., Laurel Mill Playhouse, HCC’s theater department, and of course Arts Collective.

The enthusiasm these actors brought to their work gave me such hope, and reminded me of when the 22-year-old inaugural poet Amanda Gorman read her uplifting lines on January 20:

We will not march back/

to what was/

but move to what shall be/

A country that is bruised but whole …

Perhaps watching a Poetry Moment featuring these young actors and the master poets will let a poem will take up residence in your bruised heart, and help you through the chaotic, difficult times ahead.

HoCoPoLitSo: Had you ever read poetry before?

Shawn Sebastian Naar: I have read poetry for performances (Langston Hughes, Shakespeare, Amiri Baraka, etc.) and I have read poetry recreationally for enjoyment (Maya Angelou, Shakespeare, Rupi Kaur, etc.)

Sarah Luckadoo: Yes! I was introduced to poetry at an early age and have always found myself drawn to it. My theater teacher in high school, who was also a published poet, was the driving force behind that love. Most, if not all, of the theater projects we did had some sort of poetry involved, including participating in the poetry recitation competition, Poetry Out Loud.

Chania Hudson: Yes! I’ve read poetry for HoCoPoLitSo and Arts Collective’s Harlem Renaissance event as Gwendolyn Bennett, and recently I read a few poems as Audre Lorde for Howard Community College’s Women’s Studies Salon: The Power Within virtual event.

HCPLS: If you did read poetry before, did you enjoy it?

SL: 100%! I love that poetry has this unique ability to tell full, intricate stories through its varying structures or even just a few words. It really shows how truly powerful words can be.

CH: Yes, I love reading poetry! I’ve found some of my favorite poems through working with HoCoPoLitSo.

SSN: Yes, I enjoy reading poetry. Reading great poetry is like listening to great music. When a poem or a song hits me in the right way and expresses a universal truth, it resonates deeply, and I am moved to tears or fits of laughter in the moment.

HCPLS: Did your perceptions of poetry change as we went through the project?

CH: I’ve always had a respect and love for poetry but this project turned my attention to the poet, and understanding the WHY of their poetry. It has felt like a behind the scenes look at how and why poems come to be.

SSN: Before this project, my personal selection of poetry was limited to more well-known poets or poets from school. Through this process, I’ve found some new favorite hidden gem poems, I’ve been introduced to Poet Laureates, and I even have some international poets that I’ve fallen in love with (Seamus Heaney, I’m looking at you).

SL: I’ve always enjoyed poetry, but this process has reignited the love I had for it. I hate to admit it, but I forgot what it felt like to just sit and read or listen to poetry. With the busyness from day to day and this “go go go” mentality, I’ve had a separation from it and this project made me realize how much I miss it.

HCPLS: Was there a favorite poem that you worked on (and why)?

SL: Such a hard question! I’ve honestly loved all of the poems I’ve worked on, but if I had to pick favorites it would probably be “blake” by Lucille Clifton and “Beijing Spring” by Marilyn Chin. “blake” was one of those poems that just reached out and grabbed me from the get-go … the words, the story, all of it. And I appreciated it even more when I discovered why Lucille Clifton wrote it and what she was trying to say. For “Beijing Spring” I particularly connected with it because of Marilyn Chin’s message of youth empowerment. She focuses on the innocence and determination of youth throughout history and demonstrates how they can quite literally move mountains to create change and defend their democratic rights.

CH: “Mrs. Wei Wants to Believe the First Amendment” by Hilary Tham, because it introduced me to a new perspective that I wasn’t fully aware of before reading it.

SSN: It’s tough to single out a favorite, but a couple poems of note would have to be Amiri Baraka’s “In the Tradition” and Josephine Jacobsen’s “Gentle Reader.” Baraka is one of my favorite playwrights and poets. The intensity of the passion and fire of “In the Tradition” is special. Conversely, I had never heard of Josephine Jacobsen before this project, but I love how she plays with opposites in “Gentle Reader.” The language is sensual, and the poem is sexy. Not what I expected at all from the refined Jacobsen and that is exactly what makes the poem brilliant.

HCPLS: Was there something you came across in the project that will stay with you?

CH: The majority of the poems featured will stay with me because of the way these poets have impacted their communities and the world around them. Each poem was like seeing the world through someone else’s eyes and I know that will stick with me for a while.

SSN: It feels to me that poetry gets overlooked sometimes in the arts. I’ve come across an incredible array of poets in this project and what will stay with me is the appetite for great poetry of the past, present, and future.

SL: In such an unprecedented time, it can be difficult to feel inspired or remember what good is left in the world. This project did both of those things. These poets shared stories about places, people, their lives–the good and the bad all wrapped together. What will stay with me is not only their stories, but their willingness to be vulnerable and share them. At the end of the day, we all have something to share, something to contribute and that’s pretty special.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Poetry Moment series producer

Click here to view Poetry Moments online at the Columbia Arts Channel.

Up next for the Arts Collective is their What Improv Group! and “A Valentine Affair (from afar).”

six questions with Patti Ross and Gwen Van Velsor

We asked our guest writers of the February Wilde Readings to tell us a little bit about their reading and writing favorites and habits. Get to know Patti Ross and Gwen Van Velsor here and join their reading on February 9th at 7:00 pm via Facebook!

Patti Ross is a local spoken word artist and host of EC Poetry and Prose Open Mic in Ellicott City, MD. A graduate of The Duke Ellington School for the Arts and the American University. Patti began her writing career for Rural America Newspapers. A lifelong advocate for the poor and homeless often using the pseudonym “little pi” Patti writes poems about the racially marginalized and society’s traumatization of the human spirit. Her blog: https://littlepisuniverse.wordpress.com

Who is the person in your life (past or present) that shows up most often in your writing?

PR: My ancestral mothers – both related and unrelated.

Where is your favorite place to write?

PR: In front of a window looking out at nature.

Do you have any consistent pre-writing rituals?

PR: I always hand write in a journal my first thoughts and first drafts.

Who always gets a first read?

PR: My accountability partner and a couple of other best friends. I also share the second draft and sometimes the first with my poetry critique group.

What is a book you’ve read more than twice (and would read again)?

PR: The Bible.

What is the most memorable reading you have attended?

PR: A young adult reading at the Strathmore titled Manual Cinema’s No Blue Memories: The Life of Gwendolyn Brooks for an exploration of DC’s grassroots poetry scene. Kim Roberts was the host and the poets were some of the best performance poets in the region. Marjan Naderi was/is fabulous. She is DC’s Youth Poet Laureate, holds five Grand Slam Champion titles: Library of Congress 2018 National Book Festival Poetry Slam Champion, two-time national Muslim Interscholastic Tournament Spoken Word Winner, 2018 NoVA Invitational Slam Champion, and the 2019 DC Youth Slam Finals Slam Champion. While being on the 2018 and 2019 DC Youth Slam Team, Marjan was featured in the Washington Post and NowThisHer. As the first Muslim American and Afghan woman to be announced as the Library of Congress’ National Book Festival Poetry Champion. I have heard her speak several times since then and her words still make me shiver. I love watching young adult poets perform. They share words with keen intention.

Gwen Van Velsor writes creative nonfiction and holds a degree in Special Education from the University of Hawaii at Manoa. She started Yellow Arrow Publishing in 2016, a project that supports writers who identify as women. Her major accomplishments include walking the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain, raising a toddler, and being OK with life exactly as it is. She has published two memoirs, Follow That Arrow, in 2016 and Freedom Warrior, in 2020.

Who is the person in your life (past or present) that shows up most often in your writing?

GVV: For better or worse, I have written the most about my ex-husband. We grew up together in a way, and there are infinite ways to write about and process those years.

Where is your favorite place to write?

GVV: I love to write in a cozy coffee shop that is buzzing with busy customers. It keeps me in a good balance between writing and daydreaming. I’m less likely to surf the internet aimlessly or bang my head on the table in editing distress when in public.

Do you have any consistent pre-writing rituals?

GVV: I try not to engage in too many rituals since I end up getting distracted by them versus feeling supported. My most consistent ritual is to write everything by hand first, then type it up when I’m in the mood. I find the hand/head/heart connection keeps me honest on the page. Typing somehow takes me away from that.

Who always gets a first read?

GVV: My best friend Rachael! She is always enthusiastic about what I write, no matter what, which is what I need in a first read in order to keep going.

What is a book you’ve read more than twice (and would read again)?

GVV: The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. It’s my go-to book when my writing is stagnant, it never gets old.

What is the most memorable reading you have attended?

GVV: I heard Rafael Alvarez give a reading in the basement of an art studio on a rainy night. It was a tiny crowd from Highlandtown (Alvarez’s “Holy Land”) and he was absolutely in his element. He was so passionate about his love for Baltimore, it was highly contagious.

Join Patti Ross and Gwen Van Velsor for an evening of reading and open mic on February 9th at 7 pm!

Joseph O’Neill headlines HoCoPoLitSo’s First Virtual Irish Evening

HoCoPoLitSo’s 43rd annual Irish Evening on February 19, 2021 is a creatively conceived virtual event. Featuring award-winning author Joseph O’Neill, the evening includes an introduction by Daniel Mulhall, Ireland’s Ambassador to the U.S., author Belinda McKeon serving as emcee, an Irish dance lesson with Maureen Berry of the Teelin School and musical performances by Jared Denhard, former MD. Governor Martin O’Malley, Laura Byrne and Sean McComiskey. Tickets, books, signature cocktail box available www.howardcc.edu/IrishEvening. If you need help with your order, the Horowitz Center Box Office has limited phone hours to answer your questions.

Joseph O’Neill has written four novels, most recently The Dog (longlisted for the 2014 Booker Prize) and Netherland, which received the 2009 PEN/Faulkner Prize for Fiction and the Kerry Fiction Prize. Born in Cork to an Irish father and a Turkish mother, O’Neill was raised in Mozambique, Turkey, Iran, and Holland before studying law at Cambridge. He emigrated to New York City more than twenty years ago. He is also the author of a book of short stories, Good Trouble (2016), and of a family history, Blood-Dark Track (2001). O’Neill’s stories have appeared in the New Yorker and Harper’s. He writes political essays for the New York Review of Books. “I’ve moved around so much and lived in so many different places that I don’t really belong to a particular place, and so I have little option but to seek out dramatic situations that I might have a chance of understanding,” he told the Paris Review.

The evening program, hosted on Zoom, begins with a pre-show at 7:20 p.m. Presented in a pub-like variety show format, the readings will be interspersed with music, Irish art, a dance lesson, an audience question and answer session, and a rousing sing-along. A link to the online event is $20 and several options are available. A signature cocktail kit, An Irishman in Istanbul (Jameson, cardamom, apricot and citrus), is available for pick up. Cocktail kits provide the ingredients for two drinks and must be ordered by 6 p.m. February 12 and will be available for pickup at The Wine Bin, 8390 Main Street, Ellicott City between noon February 18th through noon February 19th. Limited quantities of three of O’Neill’s books (The Dog, Netherland, and Good Trouble) are also available for purchase.

O’Neill joins the long list of illustrious Irish authors HoCoPoLitSo has brought to Howard County audiences, including Frank McCourt, Colm Tóibín, Anne Enright, Colum McCann, and Emma Donoghue. For more than 40 years, HoCoPoLitSo’s Irish Evening has celebrated the substantial impact of Irish-born writers on the world of contemporary literature.

Poetry Moment: Taylor Mali’s dose of humor

To the usual five stages of grief, poet Taylor Mali adds a sixth–humor.

These days, many of us are progressing through the five stages of grief that Elizabeth Kubler-Ross named: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

Sure, Shakespeare wrote, “To weep is to make less the depth of grief.” But what about laughter? With his poem “My Deepest Condiments,” Mali poses that humor can help one endure grief.

A four-time National Poetry Slam champion who studied at Oxford with the Royal Shakespeare Company, Mali hit it big with his poem “What Teachers Make.”

The New York Times called him “a ranting comic showman and literary provocateur.”

In his Writing Life interview, Mali cited Latin poet Horace, and his declaration that the task of the poet was to either instruct or to delight. The greatest praise, Horace said, should be reserved for those who can do both.

“I try to delight and I try to instruct. If I can’t do both of those, let me be merely delightful,” Mali explained. “The truth is that people are going to listen to the beauty of your words, and your words will find a deeper place and stay there if people can enjoy them on the way down.”

“My Deepest Condiments,” recited during his interview on The Writing Life, lingers on the small reprieves in grief that can sometimes arise.

The poem’s language–like “condiments” rhyming with “sentiments”–is playful, but the subject is serious, Mali’s father’s death. A friend’s letter of condolence arrives at Mali’s home, sending her “deepest condiments.” No one knows what to write in a sympathy card, but “deepest condiments” is probably not the best choice.

To Mali, riffing on the found poem of the card’s mistake, the gesture was “sweet relief.”

Laughter is the best medicine, so the saying goes, and this poem brings the funny, but in a bittersweet way. Because by the end, after the laughter, Mali returns to cry just a bit more.

Susan Thornton Hobby

The Writing Life producer

Poetry Moment: Poems of beauty and terror with Rachel Eliza Griffiths

Rachel Eliza Griffiths is obsessed with beauty. Not in the way that Vanity Fair or Hollywood are fixated on the way a person’s body or face looks.

Instead, she says, her relationship with beauty is “complicated.”

One of her favorite quotes is from Bohemian-Austrian poet Ranier Maria Rilke: “For beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror that we are still able to bear, and we revere it so, because it calmly disdains to destroy us.”

Griffiths’s poetry, her photography, even her film-making and visual art circles around the idea of beauty warily, both drawn to it, and shy of its terror.

“For me, beautiful things involve asymmetrical words and language,” Griffiths said. “I interrogate [beauty], I ask questions. Particularly as a photographer, I’m quite adamant and vigilant about constant questioning and revising and expanding of what it means to invoke the word, and also the practice of it, and the way that it works in language and visuals will be a lifelong trial, I think.”

This Poetry Moment features an excerpt from her longer poem, “According to Beauty.” The poem is dotted with imagery not usually associated with the beautiful, and with words such as “crawled and staggered,” “shattered,” and “splattered.” Pretty is not the same as beautiful. And in Griffiths’ poem, the beautiful is equally terrifying and gorgeous.

Her poem even interrogates the random distribution of beauty: “Luck fell silently/ through the earth. / Luck crawled wherever beautiful things lived.”

With her line, “the burden of the I within/ a flawless landscape,” the poet questions even the validity of beauty.

Featured in a fashion shoot for O Magazine in 2011, Griffiths wore a canary yellow ruffled blouse and salmon-colored pencil skirt and smiled while she mimed painting words on a wall with a javelin-sized brush.

“Gazelle you are mine. Your corpse pounds into me like music,” the words on the wall read, from her poem “Ode to a Gazelle While I Bathe on Sunday Evenings.” Beautiful and terrible, just like Rilke said.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Producer, The Writing Life

For Reference only:

According to Beauty

Under midnights you came, a hunter through memory.

It was memory that could please and betray. It was memory

that crawled and staggered, staging the deaths of beautiful words.

It was memory, distressed as a mirror, which shattered smoke. Face.

It was memory that bewildered the alchemy of the real.

I could never escape midnights or the remembering.

It was memory, a voice said. The voice belonged to everyone,

which made it into thunder. It was memory waiting in a corner

like a riff of selves in the dark. I am an outlaw woman

shadow-dancing. My life too quick to bruise. What is the name for those who collect the beautiful.

Later version:

My life too fast to burn. It was memory

that killed my loves, my children, shamed the old country.

The moon was involved wherever wolves hunted.

Stars were gathered. Arrows piercing my shoulder. Luck fell silently

through the earth. Luck crawled wherever beautiful things lived.

Through fields of water I wandered. Ishmael,

as I fled the whale-skull. What salt gave me at dawn.

There were colors, textures. Under the hood of irreparable delight,

adorned in moths, I arrived. What is the name

for those who collect the beautiful?

The word for the gesture of seeing

but not possessing eyes? Sight ghosted or exorcised. An eye

that blurs as the selves, the burden of the I within

a flawless landscape.

Starlings, from a dark cluster.

I stare at the way bars lengthen in moonlight

upon my bedroom floor where I danced in a wind

for your lungs. You held solace, a small yellow bird,

to my cheek until it stopped breathing.

Whispers uttered between memorize and believe.

It was memory that gave me faith then unleashed termites

in my house, my body. It was memory that held

the faces quiet. It was memory that marched and saluted

my useless authority, mocking my splattered skin.

It was memory that cried for blood

and vengeance. Against the midnights

where the shutters of the law remained latched.

And it was impossible to know whether God was

sleeping inside.

I told you once about the woman

I met, huddled by a river. Stained yet polished

by rain and music. I always wondered why

she waited for the moonlight to disappear

before she revealed her face,

pronouncing our name.

Miracle Arrhythmia, 2010.

https://youtu.be/Qsm4gG6cy1k

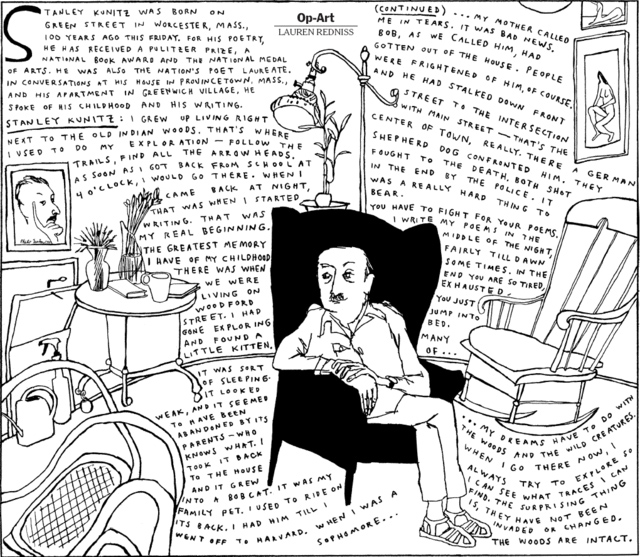

Poetry Moment: Stanley Kunitz sets us adrift from 2020

Stanley Kunitz, the lauded poet who read and wrote and gardened until he was 100 years old, spoke truth about the world—that while we’re in the midst of being alive, we’re also on the path to our graves.

“The deepest thing I know is that I am living and dying at once, and my conviction is to report that self-dialogue,” Kunitz wrote.

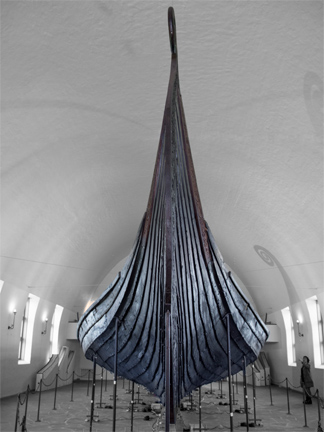

This week’s Poetry Moment captures Kunitz, at age 88, reading “The Long Boat,” his poem about a Viking funeral ritual of setting the dead on a boat and sending it adrift. He visited HoCoPoLitSo audiences during the term of his second national poet laureate appointment and recorded an interview and reading.

In Norse mythology, boats represented the Vikings’ life at sea, so the dead were sometimes placed on ships and sent out to sea, or buried in grave mounds shaped like ships, outlined in stones.

At the end of a year replete with mourning, this poem seems apropos.

“The Long Boat” hovers on the perimeter between life and death, touching on what is precious about life and also what is inevitable, even peaceful, about death. By beginning with the boat leaving the shore, and speaking in the voice of the dead man, the poem allows readers to feel great nostalgia and reluctance on leaving the world of the living, but also the contentment of slipping into death. The Viking’s burial ship is also his cradle, rocked by the waves.

Kunitz, who won the Pulitzer at age 54 and a National Book Award for work published when he was 90, said he believed the secrets to his longevity were writing poetry, being curious, digging in his garden, and drinking martinis. But it’s through his writing that readers understand the deep beliefs he held about the importance of poetry, but also the sacred nature of life.

“The poem comes in the form of a blessing—‘like rapture breaking on the mind,’ as I tried to phrase it in my youth,” Kunitz wrote in his preface to Through: Later Poems, New and Selected. “Through the years I have found this gift of poetry to be life-sustaining, life-enhancing, and absolutely unpredictable. Does one live, therefore, for the sake of poetry? No, the reverse is true: poetry is for the sake of the life.”

Susan Thornton Hobby

Producer, The Writing Life

For reference only:

The Long Boat

by Stanley Kunitz

When his boat snapped loose

from its mooring, under

the screaking of the gulls,

he tried at first to wave

to his dear ones on shore,

but in the rolling fog

they had already lost their faces.

Too tired even to choose

between jumping and calling,

somehow he felt absolved and free

of his burdens, those mottoes

stamped on his name-tag:

conscience, ambition, and all

that caring.He was content to lie down

with the family ghosts

in the slop of his cradle,

buffeted by the storm,

endlessly drifting.

Peace! Peace!

To be rocked by the Infinite!

As if it didn’t matter

which way was home;

as if he didn’t know

he loved the earth so much

he wanted to stay forever.

From Passing Through, 1995.

Photo credit:

“Oseberg Ship III” by A.Davey

Caption: In 1904, just a year before poet Stanley Kunitz was born, this Viking burial ship was discovered in a burial mound with two female skeletons and ritual funeral goods on board. It dates from before the year 800. The oak ship is displayed at the Viking Ship Museum in Norway.

Art credit:

“On Stanley Kunitz” by ChrisL_AK is licensed under Creative Commons.

Poetry Moment: Eavan Boland commiserates with Ceres

Whenever winter shakes itself awake and sheds the first snowflakes, the myth of Persephone comes to mind.

Kidnapped by Hades and imprisoned in hell, Persephone is pursued by her mother, who searches ceaselessly until she finally finds her daughter.

Though she has tried to refuse, the hungry Persephone has eaten six seeds of the pomegranate Hades has given her. The rules of hell say that if you eat or drink of the underworld’s produce, you must remain underground. But Persephone’s mother, called Demeter or Ceres, negotiates with Hades so that for half the year, her daughter emerges to stroll through the fields of flowers with her mom on Earth, and spends six months as Hades’ wife below ground, when nature sleeps and the Earth is cold. And that Greek myth explains the seasons.

But who could blame Persephone? Who could resist the gift of a pomegranate? Assertively red and juicy, almost the antithesis of winter, a pomegranate stores up all that delicious summer into a beautiful package. Greeks still hold pomegranates in high esteem, hanging them above their doors for the twelve days of Christmas, and cut the fruit for the Christmas feast table.

Eavan Boland’s poem, “The Pomegranate,” is built on the heart-breaking myth of Persephone and her mother, and the choices that teenage girls make that their mothers have to stand by and watch.

“This poem is just to register my surprise at having a child who turned into a teenager,” Boland said during the full interview with Linda Pastan.

At first, Boland’s speaker in the poem enters the myth as a daughter, but when she becomes a mother and loses a daughter at twilight, her frantic search recalls Ceres’ hunt for Persephone. “When she came running I was ready/ to make any bargain to keep her” the poem explains.

Then, when her daughter grows into a teenager, Boland’s speaker focuses on how the daughter will enter a different world as an adult, just as her mother did. These “rifts in time” allow a woman to remember what it was like to be both a daughter and a mother, gripped by the ineffable love and fear for a daughter. And by the end of the poem, readers understand what the mother has grown to know, that she cannot protect her daughter with bargains or gifts, or even words.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Producer, The Writing Life

Photo Credits:

Girl with a Pomegranate, By William-Adolphe Bouguereau, in Wikimedia Commons

An Opened Pomegranate: by Fir0002, in Wikimedia Commons

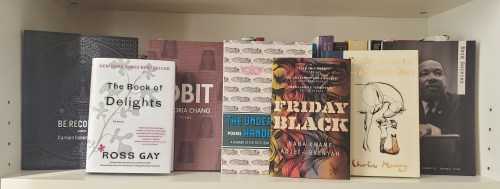

HoCoPoLitSo recommends – best books we read in 2020

[from left to right] Be Recorder, The Book of Delights, Obit, The Understudy’s Handbook, Friday Black, The Boy The Mole The Fox and The Horse, Raising King

Tara recommends Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell.

“I loved this informed, insightful journey of imagination, underpinned by a respect for historical fact, into the intimate, inner life of the Bard as seen by those closest to him. This 360 degree family perspective is a fresh, masterfully designed, and moving vehicle to further our delight in and fascination with Shakespeare.”

Pam recommends The Ninth Hour by Alice McDermott.

“The story reminded me of the role/value religious play(ed) in our community, that no one is immune from ethical decisions and our actions can have long-lasting ripple effects. The ‘best’ action(s) is not always the ‘approved’ action.”

Kathy L. recommends Talking to Strangers by Malcolm Gladwell.

“Along with an analysis of how often we make wrong assumptions about people due to unacknowledged biases, it includes a good discussion on effective policing.”

Susan recommends The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett.

The book “‘starts with a pair of light-skinned Black twins growing up in a tiny Louisiana town. They run away from home, are separated, and one of the sisters ‘passes’ as white. Their daughters’ lives eventually intersect. This novel explores the idea of recreating a self different from the one you’re born into – changing genders, races, social classes – in really interesting ways. Bennett’s book makes you think about who we are, and what defines the self, as well as leads us through forty years of American history.”

Kathy S. recommends 10 Minutes, 38 Seconds in This Strange World by Elif Shafak.

“A captivating exploration of the beauty and brutality of Istanbul through the last thoughts of a murdered woman and the response from her small community of outcast friends.”

Laura recommends The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories by Caroline Kim.

“This collection of short stories skillfully manages to be specific to Korean and Korean-American experience/perspective and at the same time universal in its exploration of love, loss, family, resilience, belonging, and crossing borders/boundaries.”

MORE RECOMMENDATIONS

Fiction

- Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah (Howard County Book Connection Book)

- A Particular Kind of Black Man by Tope Folarin

- If I Had Your Face by Frances Ha

- The Dutch House by Ann Patchett

- The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek by Kim Michele Richardson

Nonfiction

- The Book of Delights by Ross Gay

- Say Nothing by Patrick Radden Keefe

- The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse by Charlie Mackesy

- Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language by Gretchen McCulloch

- Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong

Poetry

- Obit by Victoria Chang

- Be Recorder: Poems by Carmen Gimenez Smith

- Deaf Republic: Poems by Ilya Kaminsky (The Blackbird Poetry Festival poet 2021)

- The Understudy’s Handbook by Steven Leyva (Current HoCoPoLitSo Writer-in-Residence 2020-2021)

- Raising King by Joseph Ross (Former HoCoPoLitSo Writer-in-Residence 2014-2015)

Poetry Moment: Forché and poetry of witness

Poets write a particular kind of history. While they might cite dates and names, as normal history books do, what poets record is an essence, their personal and political stories distilled into lines that evoke eras.

Poet Carolyn Forché, known for her own poems about civil war atrocities in El Salvador, spent more than thirteen years collecting work from poets around the world who had endured imprisonment, exile, repression, censorship, war.

In the 816 pages of Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness, Forché anthologized more than 140 poets from five continents, spanning history from the Armenian genocide to the massacre in Tiananmen Square. And when it was published in 1993, she coined the term poetry of witness, to denote the method of describing history that poets under extreme conditions developed.

“I was interested in what these experiences had done to the poets’ imaginations and to their language,” Forché explained. “And whether or not, regardless of the subject matter, whether one could feel this suffering and the extremity in the poems.”

The work in this week’s Poetry Moment is a tiny excerpt of a longer poem, “Requiem,” read by Forché, but penned by Anna Akhmatova. Forché remembers being captured by this poem as a student, she says, it is perhaps the reason that her anthology exists.

Akhmatova was a Russian poet and translator who survived the Great Purge and Stalinist terror, more than fifteen years of her books being banned and suppressed, grinding poverty, harassment, and threats from the state police.

While the government restricted her, Akhmatova composed her poem “Requiem.” Subject to constant danger of search and arrest, Akhmatova told the long narrative poem, line by line, to her closest friends to memorize, then burned in an ashtray the scraps of paper on which she had written her poetry.

She conceived of the poem while standing in line with hundreds of other women outside Leningrad’s prison. All carrying baskets of food they hoped to smuggle or bribe their way into their beloved prisoners, the women were waiting, like Akhmatova, to hear news of their families. One day, another woman heard that she was a poet, and asked her to get out the news about their vigil.

Akhmatova began writing. Her son was dragged from home in the middle of the night by state police because Akhmatova and his father, another subversive poet, spoke against the government. His father died in prison. Akhmatova waited outside the Leningrad prison for the seventeen months he was imprisoned there, and then at home when he was sent to a forced-labor camp. For decades she wrote in secret and hoped to see again her son, who after twenty years was eventually released and became a historian and translator.

Akhmatova chose not to emigrate, instead staying in the Soviet Union to act as a witness to the horrors around her. Because of its criticism of the purges, “Requiem” was not published in the USSR until 1987.

The Antioch Review wrote that the poems of Akhmatova, as well as the other poets that Forché collected, provide “irrefutable and copious evidence of the human ability to record, to write, to speak in the face of those atrocities.”

Forché said her anthology takes its impulse from the words of Bertolt Brecht: “In the dark times, will there be singing? /Yes, there will be singing./About the dark times.”

Especially in dark times, poets must sing.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Producer, The Writing Life