Power of Poetry – a guest post by Hiram Larew

Poetry doesn’t vote. It can’t rule. It sits on no juries. It signs nothing into law. It neither runs companies or organizes houses of worship. And, it never ever wins an Academy award or Olympic Gold Medal. Or, war. On all of these fronts that matter, poetry is powerless. And for that very reason, of course, it is incredibly powerful.

Poetry is our grins, our anger, your life, my death. It’s the birds that stitch air. It’s the soul of night, the feast of day, and that ever present caution that’s careless. Poetry doesn’t decide. It doesn’t provide. If it answers at all, it does so with questions. And, to be honest, poetry doesn’t care; it cares as deeply as wells do, yes, but it never brings you water. It wants nothing from you except wanting – this is probably its most gifting power.

And it soars, when allowed to, over just about anything else we can imagine. It’s not the clouds above so much, but our need for them. Said all at once, poetry is powerful for what it cannot be, and for the dreams it wants.

If you should ever encounter a poem that makes you jump, ask yourself why. Most likely, the answer – if there is one – will be from so far-fully inside you that ancestors will wink.

Finally, poetry is really nowhere and so it’s just about everywhere around us. It lives in the corner of your eye. It watches everything from the side. Poetry is the best glancer of all. It also aches with whatever is gone. And, it cheers – even raves – for what may never be. All to say, thank goodness – and badness – for poetry, and for our never being completely sure how powerfully potent it really is.

Hiram Larew’s work has appeared most recently in Little Patuxent Review, FORTH, vox poetica, Poetry Super Highway, Poets & Artists, Every Day Poems, Lunaris Review (Nigeria), Amsterdam Quarterly, and The Wild Word. Author of three collections, he’s been nominated for four national Pushcart prizes, is a member of the Shakespeare Folger Library’s poetry board, and organizes several events in Prince George’s County, Maryland and beyond including Poetry X Hunger and The Poetry Poster Project. He is a global hunger specialist, and lives in Upper Marlboro, Maryland.

This piece first appeared in Echo World, and subsequently in Poets & Artists, Tales from the Forest, Miriam’s Well (blog) and Huffington Post’s Thrive Global.

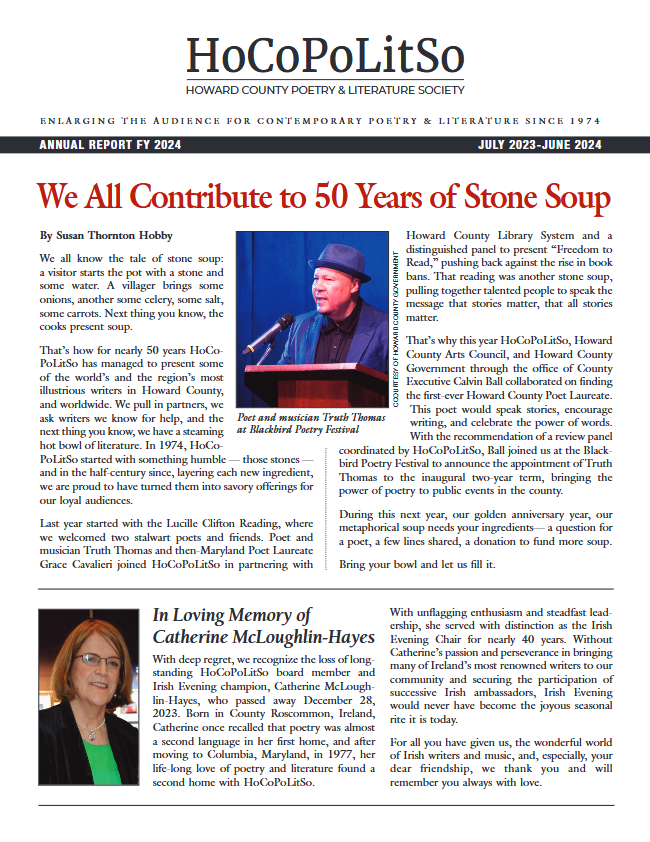

“Up Close and Personal” at the Recent Blackbird Poetry Festival

During Olympics’ coverage when I was a kid, ABC’s genial Jim McKay used to do interviews with athletes called “Up Close and Personal.” Sure, ice skating and swimming competitions were cool to watch, but “Up Close and Personal” was always my favorite because those talks felt intimate.

During Olympics’ coverage when I was a kid, ABC’s genial Jim McKay used to do interviews with athletes called “Up Close and Personal.” Sure, ice skating and swimming competitions were cool to watch, but “Up Close and Personal” was always my favorite because those talks felt intimate.

HoCoPoLitSo’s own versions of “Up Close and Personal” are the workshops that acclaimed writers offer aspiring writers. During the 2018 Blackbird Poetry Festival, featured poets Marilyn Chin and Joseph Ross read their work during the afternoon and evening. But on the morning of April 26, Ross and Chin offered forty students a close-up version of writing and reading poetry.

Students from Howard Community College’s creative writing and English courses were assigned some of Chin’s poetry to read, and she brought those poems to life, reciting and reading works like “How I Got That Name,” in which she explains how her father repurposed her Chinese name, Mei Ling, to become Marilyn. As a dark brown Chinese child, she wasn’t beautiful and wasn’t honored, Chin explained to the students.

“I’m this little Chinese girl, born dark, underweight, a little weak. How shall I speak? I shall speak loudly,” Chin said. “I shall speak for that little brown girl who was unwanted.”

“I’m this little Chinese girl, born dark, underweight, a little weak. How shall I speak? I shall speak loudly,” Chin said. “I shall speak for that little brown girl who was unwanted.”

Chin and the students also talked about “loaded words,” like “slant” and “bitch,” and how Chin wants to repurpose those words and take the power away from the negativity that bigots have used.

“You can take the power back,” Chin promised.

When Joseph Ross claimed the microphone, he turned the tables and asked the students to write. “Every poem is political,” Ross said, because as Langston Hughes wrote, “Poets who write mostly about love, roses and moonlight, sunsets and snow, must lead a very quiet life.” Whether you choose to write about sunsets or sexual assault, snow or police brutality, those are political choices, he explained.

Then he asked students to write ten to fifteen-line poems including these phrases: line from a song, a phrase someone might hear on public transportation, words someone might speak in a kitchen, and title of a favorite book or poem or movie.

Sofia Barrios, who also read a powerful political poem during the afternoon reading, wrote a poem that logically incorporated the line, “Next stop, Glenmont.”

Sofia Barrios, who also read a powerful political poem during the afternoon reading, wrote a poem that logically incorporated the line, “Next stop, Glenmont.”

The next assignment Ross suggested was to write an apology that the author wanted to hear. One student wrote the apology her father should give to her. Another wrote an apology to his inner self that included the sentiment that he was sorry he didn’t believe in himself more.

After the workshop, Chin listened to one student’s story. Chunlian Valchar told  Chin that as a baby girl born with a birth defect in China, her birth parents left her by the side of the road near the market. Valchar’s adoptive family wanted her, though, so Valchar said her situation was slightly different from Chin’s, but she still identified strongly with Chin’s work.

Chin that as a baby girl born with a birth defect in China, her birth parents left her by the side of the road near the market. Valchar’s adoptive family wanted her, though, so Valchar said her situation was slightly different from Chin’s, but she still identified strongly with Chin’s work.

Chin enfolded Valchar in a hug, they took a photo and Chin left her with a simple thought: “You’re loved and cherished.”

Afterward, Valchar explained that she’s not really angry at her birth parents, since she doesn’t really know what they were going through. But she liked Chin’s poetry.

“It’s interesting to see a poet on paper, and then to hear the background,” Valchar said. “It’s more impactful to hear the back story.”

Up close and personal indeed.

Susan Thornton Hobby

HoCoPoLitSo board member

Boys’ Book Club: How these five third graders roll

A blog post by Laura Yoo

“My favorite part of the book was when James’s parents died!” my 9-year old son Sammy yelled. And everyone around the table yelled back, “What? Oh my God! Why?” He had a perfectly reasonable response: “Because! That’s what made the whole story possible!”

Five 9-year old boys sat around the kitchen table at the home of Brooke Dalesio on a gorgeous, sunny April afternoon talking about Roald Dahl’s James and the Giant Peach. School had gotten out three hours early, and the five boys were invited to the first installment of the Boys’ Book Club organized by Brooke for her son Nate and four of his friends. Brooke is a reading specialist who currently works with education majors at University of Maryland College Park, supervising their student teaching. She also works with the reading team as a Title 1 reading tutor at the five boys’ school, Longfellow Elementary in Howard County, Maryland.

Back in February, when Brooke texted me with, “I have a crazy idea that I thought we could do together,” I responded with, “I’m scared.” She proposed to host a book club for a few of Nate’s friends, including Sammy. After a few more text messages back and forth about the logistics, I answered the call with “What the hell! Let’s try it!”

At first, Sammy wasn’t so sure. I guess he just didn’t know what to expect. He asked, “Is it like school work? It sounds like school work.” I assured him that it’d be EVEN MORE FUN than school work. Brooke got the ball rolling by emailing the moms, and Sammy started reading James and the Giant Peach. He loved it right away. When he was finished, he handed it to me (I had not yet read the book) and moved onto Fantastic Mr. Fox. He was counting the days til the first book club meeting. (I cheated by listening to the audio book of James and the Giant Peach, which I highly recommend, by the way.)

For the first book club meeting, Brooke offered fresh peach slices and peach smoothies for snack. They also munched on peach flavored gummy snacks that Sammy and I found at Lotte. While the boys enjoyed their snacks, they started the meeting by sharing general impressions of the book. They kept raising their hands – just like in school – instead of having a conversation. But that was okay – they’d need practice.

They took turns picking discussion questions that Brooke had prepared. The boys got a kick out of the question asking them to find “juicy words” from the book. They loved “ghastly,” “mammoth,” “frantically,” “brute,” and “peculiar.” (Later, one of the boys used “peculiar” in his sentence, just casually throwing it in there as if he’d always known that word.) Brooke told them about British English versus American English, and we listened to a short clip of the audio book on my phone so we could hear the accent. Other questions asked about their favorite characters, how James changes throughout the book, and about the role of magic in this fantasy novel. My favorite question, though, asked the boys to imagine other ways that James and his friends could have gotten out of some of the sticky situations during their adventures, because it encouraged creative problem solving.

After the discussion, the boys created a storyboard of the novel using a long piece of paper Brooke had prepared. They had to decide how to break up the story and how they’d represent the important events in the book. This part got a little hairy and Brooke and I offered some suggestions, but we let them sort it out. (Brooke, by the way, is much better at letting them be than I am. I’m, shall we say, much more “hands on.”) And of course they did a fantastic job.

- Part 1 of James and the Giant Peach

- Part 2 of James and the Giant Peach

- Part 3 of James and the Giant Peach

- Part 4 of James and the Giant Peach

- Part 5 of James and the Giant Peach

- The End

Brooke did the facilitating, and I enjoyed my peach smoothie and observed with fascination. I loved the level of energy in the room. The boys were excited to talk and to share their ideas. Sure, they all got a bit silly at times. Occasionally, one of them would get up and walk around the room – or dance. They talked on top of each other. Sometimes they got excited and yelled. Still, Brooke kept her cool and steered the group back to the table and back to the book. Other times, she just let them get their energy out for a minute or two. I was impressed. This was a serious level up from “playdate.”

The boys agreed on The BFG for their next book club meeting, which will be in June. After the official book club meeting was adjourned, the little literary scholars dashed outside to play basketball and soccer in the sun while enjoying peach flavored ice pops.

“It was awesome,” Sammy said to me as we left Nate’s house. He cannot wait til June. I joined my first book club when I was 38 years old, so clearly Sammy is getting a serious head start thanks to Ms. Brooke’s “crazy idea” that turned out to be quite awesome.

Lessons of Passing: Remembering Nella Larsen on her birthday

A guest blog post by Nsikan Akpan

Nsikan Akpan serves on the board of HoCoPoLitSo and is a student at Howard Community College. She is a writer, actress, and future lawyer for black rights. She enjoys reading big books and watching long movies. To read more of Nsikan’s work, visit her blog: onmogul.com/nsikan-akpan.

Characters in stories are hardly given enough credit for their bravery of taking on the task of representing the idiosyncrasies and lifestyles that the public prefers to keep private. Clare and Irene in Nella Larsen’s Passing are appropriate examples. Irene’s complexion is light enough to pass for a white woman but makes the choice to side with her true community. On the other hand, Clare, Irene’s friend from childhood, is also light enough to pass for white and finesses this fact to marry Bellew, a white racist. As readers maneuver their way through the lonely, privileged lives of both Irene and Clare, we find that wealth and passing for the sake of wealth may not be worth one’s peace of mind. It can lead to a fatal end.

Passing by Nella Larsen examines themes of hypocrisy, physical (racial) as well as social “passing,” and the sacrifices made for the American dream. Passing is a form of pretending, and sometimes we cross boundaries when playing pretend. What makes Larsen’s work significant is that it displays passing as an example of natural human desire to survive. Judging Clare equates to judging anyone that has been put in a situation where the only way out is to be something they are not. Humankind has done worse for survival. Still, Clare’s life is a lesson: one can make it to the other side and realize there is nothing there for them.

I am reminded of O. J. Simpson’s story. Simpson, a black man, had been a supreme football player, the first to run over 2,000 yards in one season. He was an athletic mogul. He helped paved the way for athletes to not only play the sport of their choice, but to do so while starring in movies, commercials, and gaining fortune from various endorsements. He was treated as an American hero and embraced by white America. If Larsen’s Clare had her pale skin that allowed her to pass as white, Simpson had wealth and his white wife that made up for his chestnut skin color and allowed him to pass in white society. In 1978, Simpson starred in a famous Hertz commercial, running through an airport as people – notably, all white people – cheered him on. “Go Juice, go!” They hailed. Until they stopped. In 1994, Simpson was accused of murdering his ex-wife, Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend, Ron Goldman. When Simpson was accused of murder, he became black again.

Passing is seductive. Joe Bell, a childhood friend, said of Simpson, “He is seduced by white society.” In Larsen’s novel, Clare was seduced enough to want to be a part of that society, so much so that she became a part of it. As examples of passing – physical and social – Clare and Simpson demonstrate that passing does not turn out well in fiction or in real life. In Larsen’s words, Clare “had been there, a vital glowing thing, like a flame of red and gold. The next thing she was gone.”

While reading Passing, I realized that there are many types of passing. I have come to recognize my own privilege of intellectual passing. I am an educated and cultured black woman who has sat next to distinguished authors and poets. These stimulating cerebral experiences allow me to go into spaces where my color is not considered because my ability to articulate trumps any stereotype that is connected to me. Or so it seemed. It turns out that intellectual passing connects very much with racial and social passing. We must put an end to associating intelligence with whiteness.

I have made a conscious choice not to give into passing. What Clare showed me is this: One can fool people with skin but not with soul. Throughout high school, despite my dark skin, I made myself “more palatable” for my white counterparts. Every time I had an opinion on something, I tried my best to express it very nicely, or sometimes I’d say nothing at all, knowing people might take it the wrong way. Fortunately, I have grown out of that nonsense. I am who I am. An exit is always available, but for me, passing is never an option. It’s too exhausting. In my own skin, I am at rest.

Expanding and Deepening the Reading List

A blog post by Laura Yoo

Expanding and Deepening the Reading List: How Centennial Lane Elementary School is providing diverse books to its students

“All children and young adults deserve excellent literature which reflects their own experience and encourages them to imagine experiences beyond their own.” – Cooperative Children’s Book Center

One afternoon when my son was 4 years old, he began to jump up and down excitedly while watching TV. He was screaming, “Mommy! She’s talking in Korean!” Indeed, a cat-like animal in a cartoon called Littlest Pet Shop was speaking in Korean while the other animal and human characters tried to understand her. The Korean-speaking animal was a ferret named Jebbie Cho who later meets a recurring Korean character on the show, a human named Youngmee Song.

My son hears Korean all the time at home, spoken by his grandma and by mommy and daddy when they don’t want him to know what they’re saying. But seeing Korean characters and hearing Korean names on TV was special. His family’s cultural identity was being reflected back to him. He saw himself. And what I saw on his little face was a sense of validation and pride. What I witnessed was the power of representation.

At Centennial Lane Elementary School in Ellicott City, Maryland, parents, staff, and teachers understand this power of representation, particularly as it is reinforced in children’s books. With the support of school staff and teachers, the members of the CLES PTA’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Committee created a book list with 70 titles that represent various nationalities and heritages as well as LGBTQ, dis/abilities, and religions. Many of the books also explore diversity as a general theme.

The CLES DEI BOOK LIST includes titles like Out of My Mind by Sharon Draper, a GR 4-6 book about an 11-year old girl with a photographic memory and cerebral palsy; Skin Again by bell hooks, a GR K-4 book about skin – about what it is and what it isn’t; and The People Shall Continue by Simon Ortiz, a GR 1-5 book about the history of Native Americans. The CLES’s list demonstrates a wide definition of diversity and aims to be as inclusive as possible.

“[It’s important] the kids see themselves in those books,” says Sabina Taj, the chair of the committee. The project, which is coordinated by Anu Prabhala, has received a donation of $500 from a parent to achieve the goal of purchasing some of these books for the school’s media center. The committee’s work has been supported by CLES Principal, Amanda Wardsworth, and the list of books has been reviewed and approved by the school’s Media Specialist, Marnie Beyer. “This was truly a labor of love,” says Ying Matties, a member of the DEI Committee.

“I’m hoping each school asks the diverse populations of the individual school and teachers to use this process as a model to create their own,” says Ms. Taj. She emphasizes the importance of focusing on community involvement in gathering ideas and feedback from various stakeholders. Then, she says, the various lists compiled by many schools could be combined to create an even more comprehensive and representative sample of books for the students in Howard County.

This vision reflects a national debate and discussion about representation in children’s books. A national non-profit organized called We Need Diverse Books, founded by YA and MG writer Ellen Oh, envisions “a world in which all children can see themselves in the pages of a book.” There is tremendous power in seeing what is possible. As Marian Wright Edelman famously said, “You can’t be what you can’t see.” This idea was reiterated when Misty Copeland became the first African American to be named principal dancer for the American Ballet Theatre and when Sheridan Ash set up a program for PwC called Women in Tech. When the Time Magazine published its “Firsts” issue about female firsts, they titled it, “Seeing is Believing.”

However, at Centennial Lane Elementary School, it’s not just Muslim children or children with two dads who will benefit from reading these books. As B.J. Epstein, professor of literature who researches and teaches children’s literature, writes in The Conversation, “Research on prejudice shows that coming in contact with people who are different – so-called ‘others’ – helps to reduce stereotypes.” So, the effect is twofold: children will learn about themselves and children will learn about the experiences and lives outside their own. Duncan Tunatiuh, author and illustrator, notes in Language Arts, “we need multicultural books so that different kinds of children can see themselves reflected in the books they read, and so that children can learn about people from diverse backgrounds and cultures.”

The Diverse Books project at Centennial Lane Elementary School is one of the various ways that parents, staff, and teachers are trying to encourage and implement curriculum that is diverse, equitable, and inclusive. The DEI Committee is also currently working with the school administration on organizing Community Circles, a venue for diverse parents to provide in-person feedback to the school on how to make it more inclusive to all its constituents.

Note: To learn about setting up a DEI Committee in your school, please contact Sabina Taj <sabinataj@gmail.com>. For more information on the CLES DEI Committee’s work, please contact Anu Prabhala <prabhala.anu@gmail.com>.

Joelle Biele brings poetry alive for HoCo students

a blog post by Anne Reis, HoCoPoLitSo Board Member

Poetry is alive and well at the Homewood Center, Howard County’s alternative school. I know this to be true because I am Homewood’s Media Specialist and for the past 10 years, with the support of HoCoPoLitSo, I have been able to host poetry workshops in my library.

Students who attend Homewood have not succeeded in the comprehensive school environment. Poetry gives these students a safe and therapeutic way to express themselves and exposes them to the power of the written word. The transformative power of poetry was never more apparent than earlier this year when HoCoPoLitSo’s Writer-In-Residence, Joelle Biele came to our library for a visit.

Students who attend Homewood have not succeeded in the comprehensive school environment. Poetry gives these students a safe and therapeutic way to express themselves and exposes them to the power of the written word. The transformative power of poetry was never more apparent than earlier this year when HoCoPoLitSo’s Writer-In-Residence, Joelle Biele came to our library for a visit.

From the moment that she greeted the students with her calm spirit and razor sharp intellect, she engaged them in a different way of thinking. With so much emphasis in school curriculum on STEM related subjects, students are rarely given the space or the time to think creatively.

Ms. Biele began her presentation by literally opening the space in the room with a Youtube video of Sandhill cranes migrating. The peaceful images of cranes in flight gave our students a moment of Zen and the background knowledge that they needed to understand her poem, Autumn. Ms. Biele challenged our students to think about what it means to write and the types of writing that they do in their daily lives. Is a text writing? Can a Facebook post be poetry? And from where does a writer find his or her voice?

Students were also asked to respond to the prompt called “I am.” Such an important question for every young person, and perhaps even more important for the struggling learners at Homewood: Who Am I? Who asks students such questions and who cares about their answers? The answer is loud and clear: poets!

For many of the students at Homewood the time spent with Ms. Biele was their first encounter with a poet, but hopefully it won’t be the last.

mana’s musings: celebrating marilyn chin on international women’s day

a blog post by Laura Yoo

It was my very first visit to the famous Dodge Poetry Festival. It was Saturday, October 22nd in 2016, right around 7:15 in the evening. There stood on this enormous stage at the New Jersey Performing Arts Center a petite Asian woman, speaking with a slight accent and a lot of voice. She read her poem, “One Child Has Brown Eyes.” First I googled “vacuity.” Then, I was mesmerized. Also on stage were poets like Martin Espada, Robert Haas, Claudia Rankine, and Jane Hirshfield, but it was Marilyn Chin who spoke to me that night. She was smart, powerful, and funny – and she looked like me.

Ever since getting a serious high on Macbeth in high school, I’ve been studying and loving English literature. In college, I chose all of my electives to be in English literature, and I studied abroad in England to nerd it up with Shakespeare and Jane Austen – and to drink a lot of beer. My area of study was eighteenth-century British literature (which even other English majors didn’t want to touch) so I can say for sure there were no likes of Marilyn Chin in my curriculum. In the last 10 years, thanks to HoCoPoLitSo, I’ve met many wonderful writers and poets, and among them a few Asian American writers, too. But the poet embodied and represented by Marilyn Chin was something new for me.

See, I always wanted to be like Sandra Oh’s character in Grey’s Anatomy, someone who wasn’t on the show to play Asian. She was just another doctor, who happened to be Asian. Her name wasn’t Johnson or Smith. Her name was Cristina Yang, best friend to the main character, but the “Yang” part did not define her character. Sandra Oh, who is Korean-Canadian, plays this “best friend” role also in Sideways and Under the Tuscan Sun. In both of these movies, she is just the best friend, not the Asian best friend. I applauded these characters. Yes! Finally! Asian people are just people! In retrospect, however, I am seeing that in some ways this is denial, a kind of self-imposed erasure. Yes, it hurts to be locked inside the limits of stereotypes, but it also hurts to deny my self from myself in an apparent fight against such stereotypes. At this point, I can hear a frustrated voice saying to me, “What do you want, then? You want Cristina Yang to be Korean or not?” Well, I think I want Cristina Yang to be her self, all of the things that she is.

Recently a Korean-American writer, Mary H.K. Choi, posted this:

From this post, I suspect that, like me, Ms. Choi has been struggling – maybe unbeknownst to her – with her relationship to the Korean part of her “Korean-American” identity. So, I have been thinking about my own going home (or coming home) and how art helps me on that journey. A great example of such art is Ms. Chin’s novel, Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen, which Sandra Cisneros called “bad ass,” Maxine Hong Kingston “What fun!” and Gish Jen “Deeply provocative and deeply Chinese.” The story of two Chinese girls growing up in California focuses very much on their grandmother’s voice and legacy, weaving 41 separate stories together into what Ms. Chin calls a “manifesto.” The story is magical, mythical, and yet so very painfully and beautifully real. The opening story is heartbreaking, shocking, and ultimately triumphant.

Ms. Chin’s poem, “How I Got My Name: An Essay on Assimilation,” is another good example. It starts like this:

I am Marilyn Mei Ling Chin

Oh, how I love the resoluteness

of that first person singular

followed by that stalwart indicative

of “be,” without the uncertain i-n-g

of “becoming.” Of course,

the name had been changed

somewhere between Angel Island and the sea,

when my father the paperson

in the late 1950s

obsessed with a bombshell blond

transliterated “Mei Ling” to “Marilyn.”

And nobody dared question

his initial impulse—for we all know

lust drove men to greatness,

not goodness, not decency.

And there I was, a wayward pink baby,

named after some tragic white woman

swollen with gin and Nembutal.

My mother couldn’t pronounce the “r.”

The assimilation happens with the choosing of an “American name.” I am also named after a white woman, Laura Ingalls Wilder, but more accurately the character Laura Ingalls on Little House on the Prairie the TV show. My mom had watched this show in Korea and loved the character. This custom is seen as practical as it is difficult for Americans to pronounce Korean names. Luckily, my family – like most Korean people – also could not pronounce the “r” and has always called me Yoonji, by my real name. Now, my little sons hear my mom calling me Yoonji and once in awhile, very quietly, they test it out in a kind of whisper “Yoonji” and then giggle. It’s like they’re wondering, “Who is this Yoonji? She’s like a whole another person from my mom who is Laura.” Maybe so. Maybe not. All of this, of course, is not to deny the name Laura, which my mom gave me and therefore an important part of my identity. Besides, it’s a beautiful name. But it’s complicated, you see.

I know it sounds cliche to say this, but Ms. Chin’s poetry, novel, and her performances have raised my awareness. No, it did not happen like a bolt of lightning or anything that dramatic, but rather like a gradual stewing and simmering in this idea about who I am and what I am. So, on this International Women’s Day, I want to thank her for being on that stage on that day at Dodge Poetry Festival to help me widen the way I might think about my cultural identities.

I am ecstatic that I will have another chance to meet Ms. Chin and maybe – if I have the guts – thank her in person on April 26th when she reads at the Blackbird Poetry Festival at Howard Community College. Read more about Marilyn Chin’s visit here.

mana’s musings: Step Aside, Ambien! Here comes Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book!

A blog post by Laura Yoo

I did not grow up with Dr. Seuss because by the time I came to the United States from Korea, I was already 10 years old and my parents certainly didn’t know who Dr. Seuss was. That’s right. I had a Seuss-less childhood.

It was when I was in high school and doing a lot of babysitting that I came across Dr. Seuss. The children just loved his books, almost as much as they enjoyed watching Disney movies. I learned quickly that Cat in the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham were some of the kids’ favorites. As a 15 year old, I didn’t see the real value of these books, of course. They were just fun.

Now as a mom to young children, a teacher of writing, and a human fascinated by language and literature, I have a whole new appreciation for Dr. Seuss. Hop on Pop, The Lorax, The Cat in the Hat, and Green Eggs and Ham are probably some of the most popular of Dr. Seuss’s books. My own two boys say Fox in Socks and One Fish Two Fish Red Fish Blue Fish are their two favorites.

While all these are wonderful stories, my personal favorite is Dr. Seuss’s Sleep Book. This is the book that truly showcases Dr. Seuss’s genius.

Oh boy, does it work. Try to stifle the yawn while you read it. You can’t do it. At least half way through, someone – you or one of the little listeners – will yawn. And once that first yawn comes out, there’s no stopping the flood of yawns to come. As Dr. Seuss says: “A yawn is quite catching, you see. Like a cough.” Turns out – just reading the word “yawn” or seeing illustrations of creatures yawning will make you yawn. That’s how powerful a yawn is.

So, by the time you reach the end of the book to read “When you put out your light, / Then the number will be / Ninety-nine zillion / Nine trillion and three” I swear the little ones look sleepy – and I am also sleepy.

And this is one of the many magical powers of Dr. Seuss. Yes, the silly names, the nonsense words, and the insane rhymes are so fun to read. Yes, the books have valuable life lessons. In addition to all that, it will help your kids go to sleep. Now, if he had just written a book called Dr. Seuss’s Clean Up Your Room Book…

Happy Dr. Seuss Day!

Presenting Marilyn Chin — Tenth Annual Blackbird Poetry Festival — April 26

The Fierce Revolution of Marilyn Chin

HoCoPoLitSo and HCC’s Tenth Annual Blackbird Poetry Festival

Marilyn Chin

Award-winning poet and author Marilyn Chin headlines the tenth annual Blackbird Poetry Festival for HoCoPoLitSo and Howard Community College (HCC). Born in Hong Kong and raised in Oregon, activist poet Chin unflinchingly explores the intersection of the Asian and American worlds.

The Blackbird Poetry Festival, held April 26, 2018, on the campus of Howard Community College, is a day devoted to verse, with student workshops, book sales, readings, and patrols by the Poetry Police. The Sunbird poetry reading, featuring Ms. Chin, as well as Washington, D.C., poet and educator Joseph Ross, local authors, and Howard Community College faculty and students, starts at 2:30 p.m. Ms. Chin will read from and discuss her poetry, including her most recent work, Hard Love Province, during the Nightbird Poetry Reading, starting at 7:30 p.m. in the Smith Theatre of the Horowitz Center for Visual and Performing Arts. Hard Love Province won the 2015 Anisfield-Wolf National Prize for Literature that confronts racism and examines diversity. Former winners of this prize include Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, Toni Morrison and Maxine Hong Kingston, Gwendolyn Brooks and Oprah Winfrey. Nightbird admission tickets are $20 each (seniors $15 and students $10). Click here for tickets.

Marilyn Chin co-directs the MFA program at San Diego State University and has won numerous awards for her poetry, including from the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, Stegner Fellowship, the PEN/Josephine Miles Award, four Pushcart Prizes, the Paterson Prize, and many others.

Chin is the author of four poetry collections: Hard Love Province (2014), Rhapsody in Plain Yellow (2002); The Phoenix Gone, The Terrace Empty (1994); and Dwarf Bamboo (1987). She is also the author of a novel, Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen (2009). Pulitzer Prize-winner and Anisfield-Wolf juror Rita Dove noted about Hard Love Province, “In these sad and beautiful poems, a withering portrayal of our global ‘society’ emerges – from Buddha to Allah, Mongols to Bethesda boys, Humvee to war horse, Dachau to West Darfur, Irrawaddy River to San Diego.” In his review of The Phoenix Gone in The Progressive, Matthew Rothschild said Chin “has a voice all her own — witty, epigraphic, idiomatic, elegiac, earthy…She covers the canvas of cultural assimilation with an intensely personal brush.” Booklist contributor Donna Seaman described the tone of Rhapsody in Plain Yellow as “Chin paces the line demarcated by the words Chinese American like a caged tiger, fury just barely held in check.”

Joseph Ross

Joseph Ross’s newest collection of poems, Ache, was published in 2017. Sarah Browning, director of Split This Rock, noted “The poems in Ache do just that, they ache – from the wounds inflicted by racism, from history’s ravages. The wail, the poems insist, ‘is the language/inside every tongue.’ Joseph Ross’s moral vision is unsparing, truth-telling, fierce.”

A teeny bit of corporate evil cuts into the HoCoPoLitSo budget

Google started with a good motto: “Don’t be evil.”

A new policy on the Google-owned YouTube channel though, seems like a teeny bit of corporate evil to thousands of small, independent channels.

The new policy, announced this week, forbids smaller channels to monetize their videos – earning pennies per view – because they don’t have enough subscribers or time that viewers watch their videos.

YouTube sent HoCoPoLitSo an email Jan. 17 that read as follows:

Under the new eligibility requirements announced today, your YouTube channel, hocopolitso, is no longer eligible for monetization because it doesn’t meet the new threshold of 4,000 hours of watchtime within the past 12 months and 1,000 subscribers. As a result, your channel will lose access to all monetization tools and features associated with the YouTube Partner Program on February 20, 2018 unless you surpass this threshold in the next 30 days. Accordingly, this email serves as 30 days notice that your YouTube Partner Program terms are terminated.

Grammatical errors aside – and those truly bother us literary types – the announcement is another cut that the arts cannot afford.

HoCoPoLitSo uses its YouTube channel to show editions of its writer-to-writer talk show, The Writing Life, featuring conversations with Nobel and Pulitzer winners, with local poets made good, with beloved authors like Lucille Clifton and Frank McCourt and Amiri Baraka who have died. Often, we have the most extensive interviews with writers like Gwendolyn Brooks; that’s because HoCoPoLitSo’s founder Ellen Conroy Kennedy had the foresight to begin recording the show to preserve – in a kind of literary time capsule – the moments of writers talking about their craft. Here is a smallest sample, the wonderful Stanley Kunitz talking about the value of poetry:

In a little more than a month, HoCoPoLitSo will be removed from the possibility of making tiny amounts of money on these shows that help fund the taping of new shows, like the one just uploaded featuring Laurie Frankel, and the digitization of archived shows, such as the Michael Longley and Edna O’Brien vintage gems that hit YouTube this week. HoCoPoLitSo usually makes only a few pennies per view, but in this current climate of reduced funding for the arts, HoCoPoLitSo needs every penny. YouTube revenues added a few hundred dollars a year to the budget; that amount could fund a visit by HoCoPoLitSo’s writer-in-residence to a high school.

What can literary lovers do? It’s not too hard. Help us reach the goal of 1,000 subscribers – the channel has 890 now – and 4,000 hours of watch time in a year. Subscribe. Try one episode of The Writing Life while you’re folding laundry or doing your New Year’s resolution sit-ups; Frank McCourt will make you laugh with stories of his Irish childhood, Tyehimba Jess will cause a brain explosion explaining and reading his three-dimensional poetry from Olio, dear Lucille Clifton will warm your heart and put a fire in your gut on five different episodes. Think of the time as a creative respite from the chaos of business and politics. And, as always, donate to help our small nonprofit bring literature to this capitalistic world, which sorely needs it.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Recording secretary and

YouTube channel manager

To subscribe to HoCoPoLitSo’s YouTube channel, click here and then click on subscribe (it’s free).