Home » Guest post

Category Archives: Guest post

an invitation to your first (or 264th) poetry reading

by Laura Yoo

I know that poetry has a reputation for being “highfalutin” and hoity toity. I know that some poems are hard and they seem utterly unreadable or unknowable. As I have confessed elsewhere before, even as an English major in college, I avoided taking the required poetry class until the very last semester.

But hear me out. Not all poetry is scary. I promise. Lots of poems are very readable and knowable. Often, poems tell stories, sometime really gritty, raw, and real stories about being human. They tell stories, whether they are fictionalized or based on the poet’s life, about how people live, exist, survive, love, and die. Different people turn to poetry looking for different things, and I turn to poetry for their poignant, particular storytelling.

So, I want to invite you to HoCoPoLitSo’s Nightbird event on April 27th with poet Noah Arhm Choi, the inaugural winner of HoCoPoLitSo’s Ellen Conroy Kennedy Poetry Prize in 2021, and hear their stories.

In Cut to Bloom, Choi’s poems tell stories about family, umma (mom) and appa (dad), hurt, violence, love, language, self discovery, and names. This one about forgiveness stays with me:

Yes, it’s a story about “queer Asian Girls” but it’s also about mothers, daughters, weddings, love, and forgiveness – all things that many of us can relate to.

How about these lines about being worthy?

Most days, it is hard to remember

I am worthy to be loved, even without

the right answer, the right joke,

the right moment.

And yet, here is my wife,

trying to tell me

a story around her toothbrush,

bragging about me to her parents,

bringing my favorite dessert home, as if

I could still be an unpredictable ending

that she wants to see unfold.

Haven’t we questioned our worthiness? Haven’t we also been loved in this way too – or have craved for such love? Is this not a story that many of us are familiar with?

When asked what they are working on after Cut to Bloom, Choi said this:

I’m working on a 2nd poetry manuscript that has been orbiting around my father’s death in 2020, my divorce, and finally coming out as transgender and beginning to transition. Sometimes I wonder what will be the thread that ties all of these subjects together. Today that thread is a look at what it means to start over and again, how grief brings out truth even if its unbearable, how much life can change in unexpected ways when one claims themself.

Are these – starting over, grief, life changing in unexpected ways, claiming oneself – not the stuff of our stories?

What I am trying to say is that you should come out to hear Noah Arhm Choi “unfold” their stories on stage on Thursday, April 27th at Monteabaro Hall at Howard Community College. Get your tickets right here. If you are a student (HCPSS high school or HCC), it’s free!

Whether this is your first poetry reading or your 264th poetry reading, you are all welcome to “poetry of belonging.”

Noah Arhm Choi is the author of Cut to Bloom (Write Bloody Publishing) the winner of the 2019 Write Bloody Prize. They received a MFA in Poetry from Sarah Lawrence College and their work appears in Barrow Street, Blackbird, The Massachusetts Review, Pleiades, Split this Rock and others. Noah was shortlisted for the Poetry International Prize and received the 2021 Ellen Conroy Kennedy Poetry Prize, alongside fellowships from Kundiman, the Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and the Martha’s Vineyard Institute of Creative Writing. They work as the Director of the Progressive Teaching Institute and Associate Director of DEI at a school in New York City. Jeanann Verlee, the author of Prey, noted “Cut to Bloom is neither delicate nor tidy. This immense work both elucidates and complicates ethnic, generational, and gender violence, examining women who fight for their humanity against those who seek to silence―indeed, erase―them.”

On Reading the Poems of Molly McCully Brown: I Hope You’re Uncomfortable

by Sama Bellomo

For me, good poetry hurts. A successful poem reignites my anger because candlelight vigils don’t.

For her poetry collection Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded, Molly McCully Brown read, with tremendous empathy, through piles of misguided clinical notes and was compelled to relay to the current generation what horrific prescriptions and outcomes were thought of as successful containments or even rehabilitations. She turned those dehumanized clinical notes back into people, people who were forced, aggrieved, and lost to history.

Usually, when being made aware of dark histories, it may seem that the right thing to do is to condemn past tortures that took place as a reality of our past and say a kind word about hard-won basic human rights that are fought for by unknown collectives of grassroots activists inspired by the late Dorothea Dix. But in the perfect medium of poetry, Brown says this is not a museum: her poetry says, this is present. Her poems have us looking back as if looking down the barrel of a gun, looking until we too empathize, until we understand that this could have been any of us, and that there is much left to be done.

With Susannah Nevison, Brown wrote In The Field Between Us, poems that read like a series of letters between two people living with disability in the contemporary world. They illuminate and explore dissociative trauma; difficulties in relating to the world, in connecting with others beyond the safe exchange they’ve created for one another. They include ruminations on being anywhere else than here; attitudes of self, and so many more deep, powerful feelings that enrich and sustain the human psyche, especially anyone enduring life with a disability.

The book begins with aftermath and carries through to pre-op, beginning sort of in medias res, where details become apparent only in hindsight. The abstractions rise as the dialogue carries on, exchanging communications of experiences in an increasingly romantic tone as everything seems to fall apart.

People with disabilities, the providers who treat them, and the general public are the same in how upset we become when faced with human fragility. We see fragility first, then we become frantic and look for stability. People with disabilities are often accustomed to advocating in the opposite direction, beginning with the strengths that will keep a listener grounded. Brown and Nevinson commit to that order by running the chronology in reverse.

The poems employ plenty of concrete and metaphorical imagery to bring the reader closer, whether they can picture the situation or not. In the aftermath of a catastrophic medical event, numbness is described as “a quiet fire.” In an early poem, we hear of a “pain, as familiar as a fist I know,” reminding me of the certain interruptions to order when pain arises and must be reckoned while the rest of life waits, in purgatory. The next letter replies: “when we sleep, of course / we become unraveled: it’s only fair”. Of course we do. Parts of ourselves get lost, suspended, denied.

Brown’s work gives resounding voice to people whose voices and stories were otherwise lost, often in the guise of merciful and humane treatment. I hope you’re as uncomfortable as I am because it’s appropriate to be uncomfortable, to be moved towards just action and a better world for every body.

Sama Bellomo has worked with agencies and individuals with disabilities as a patient navigator and advocate with Patient Providers (www.ptprov.com).

Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded by Molly McCully Brown

In The Field Between Us by Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison

On Reading: What’s In A Name?

There’s quite a stack of things that I have set aside ‘to read next’, whenever that comes along. More and more gets added to the stack and each book slowly waits its turn, probably too patiently. Every once in a while something comes along that moves right up to Next and becomes Now already. Never did I imagine a document on the naming of public spaces commissioned by our County Executive Dr. Calvin Ball to slip into the queue, much less become next and now as soon as I heard about it. It is an absolute must read, and a riveting page turner at that. I can’t look away, and I shouldn’t.

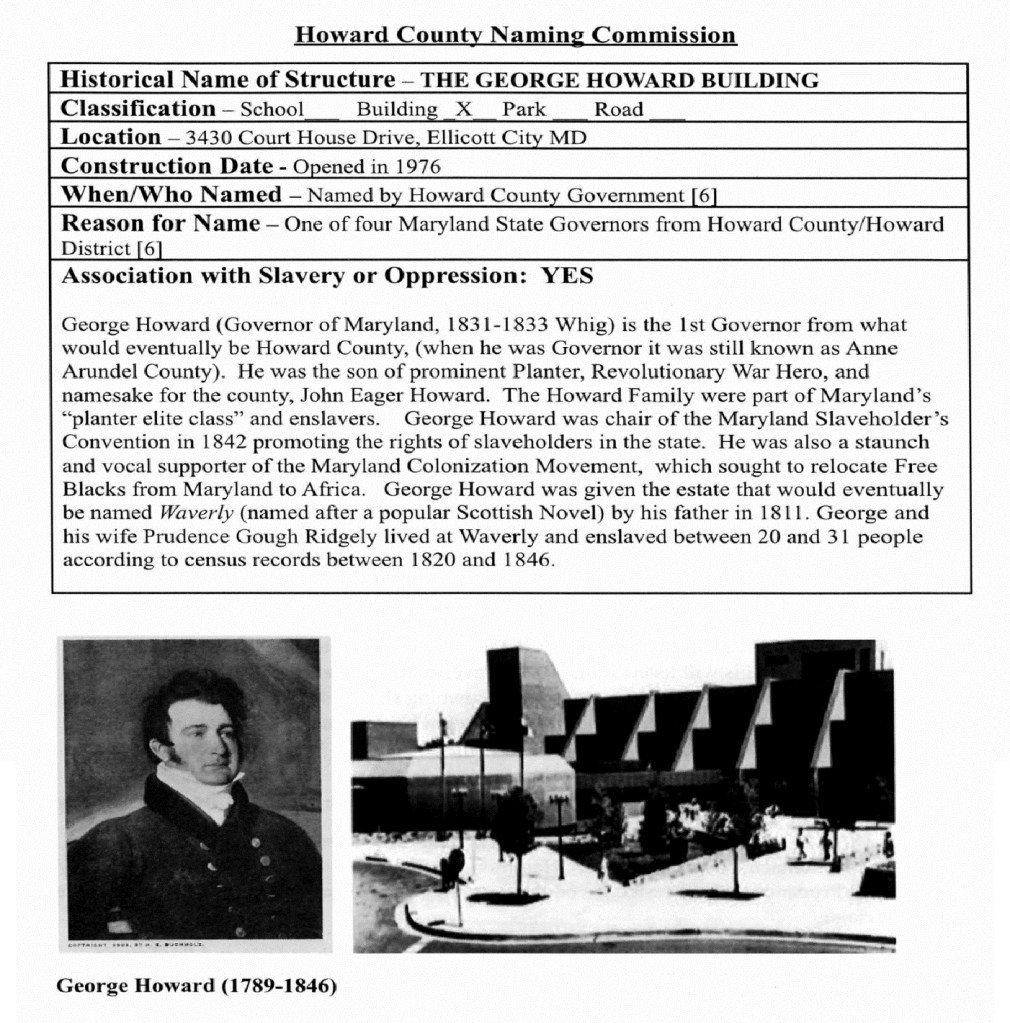

The document is the 262 page Public Spaces Commission Report, released on November 5, 2021. It lists out all public owned buildings in Howard County, Maryland, where I live, their names, and the relation of the person behind that name to any history of slave ownership and/or oppression. It documents participation in slavery, involvement in systemic racism, support for oppression, involvement in a supremacist agenda, violation of Howard County human rights laws, and even if the namesake includes racist and offensive terminology. It is pretty weighty; here is an example:

Wow. Page after page of analysis and detail like this, building after building. For a number of buildings, no direct relation to slavery was discovered, for many, though, there is a past to reconcile.

These buildings have an everyday presence in our lives: government administration buildings, schools, parks, libraries and such (the report put off addressing the 3,000+ street names in the county for another day). Building name elements are familiar and roll off our tongues like nothing matters: Warfield Building, Miller Branch, Atholton Park, River Hill, and so on. For many of us today, any association with history, benign or otherwise, is not really part of our everyday interaction. Places become more associated with what we do there, like attend a meeting, pay a ticket, check out a book, swing on a swing set. Knowing only so much, those that stop and think about it may take a moment and realize, “Oh, so that’s who the George Howard Building was named after, the first governor of the state from our county… interesting.” Up till now, that might have been the depth of curiosity, recognizing a bit of historic trivia.

Less trivial, and what this document lays out page after suffocating page, is a deeper understanding of our county’s past and its people of power or note now memorialized through building names: that they enslaved and profited so off of others. For locals who know these buildings and so casually say their names, it is jaw dropping. We Howard Countians must deepen our understanding of the past in our present, and begin a discussion about how to reconcile with it. This is a start.

This report really is vital knowledge. You can find and read or browse the Public Spaces Commission Report here. Seriously, take a look… you won’t be able to look away. Sincere thanks to this administration for commissioning it and bringing forward this part of Howard County history, and special thanks to the researchers behind the project (all are listed within the report). What a document you have made, what an important resource. As one would expect, the work does not stop here.

My Own Name. I have another reading project in the works, one that is going to come sooner after reading this report. I want to understand my own name, and its relationship to slavery. The Singletons originally came into this country in the 1700s and established a cotton plantation up river from Charleston, South Carolina. I hear they were also later successful in North Carolina. That they were successful means they relied on the work of slaves, the lives of slaves. I want to know more about that, to understand and document what is in the name I wear, the one that has been carried superficially into the present, a little too willfully unaware. As you know me, the project will start with reading, with books like Edward Ball’s Slaves in the Family, a model for the research, and Theodore Rosengarten’s Tombee, A Portrait of a Cotton Planter already in the queue, move through google search results of my own name, and eventually a trip south to visit places in person. It is a monumental task, but it will be a task that builds a more real monument to those that came before us and how they lived prior to our becoming. We owe it to them.

I usually end these with ‘Happy Reading’, but this is a different kind of reading.

Sincerely,

Tim Singleton

Board Co-chair, HoCoPoLitSo

Further reading for Howard County history buffs: History of Blacks in Howard County Maryland, Oral History, Schooling, and Contemporary Issues, by Alice Cornelison, Silas E. Craft, Sr., and Lille Price, published under the auspices of the Howard County Branch of the NAACP in 1986.

On Reading: Reading Through a Pandemic

You would think one might plow through books during a pandemic, making the most out of quarantine and isolation. Truth be told, that’s not what this reader found to be the case. I stalled. I plodded. Mostly, I couldn’t.

While I didn’t stop reading all together, I find I have read far less books than I might have in more normal years. Hardly a day goes by where I don’t consider that, wondering what it will take to get back up to a speed to take on all the beloved unreads on my bookshelves. There’s lots of learning to do and make useful.

The way I described it early on was that I had ‘lost my metaphysics’. I couldn’t, out of habit and reflex, rely on things the way I had before. I was in a mindfog. Others described ‘languishing‘. The reliable patterns of how life was lived and days were made was gone, and something of identity and well-being along with it. Forced into the very present moment, words seem to lose their heritage, meaning and purpose. They ceased to connect. The dependable way things were failed as normal gave way to the behavior change the lethal spread of Covid demanded (and, alas, still warrants).

The very moment of quarantine shutdown, I was writing an article about an artist whose work is often commissioned for public spaces, the cover story on Katherine Tzu-Lan Mann for an issue of Little Patuxent Review. I had just finished interviewing the artist, and had the piece settled in my head. It only wanting typing out. It should have been an easy thing to do as lockdown started and I would have some time, but I started to realize that I had to write a completely different piece than what was in my mind — how does one visit and view public art when one can’t, what does that say about art and experience, what of public art and place in particular? I began to realize that the underlying foundation to what I wanted to say no longer held sway. The piece became an altogether different consideration. I was stifled and it took me a while to ‘come to terms’ and write it.

Words have definitions that come from long development and understanding (agreed upon, or not). In a sense, they are The Past, and our reliance on the past in the way we now live. They connect us in this way. Along comes the pandemic and the every day way things used to be is no longer the way things are. For me that was particularly unsettling. Pushed into the present moment, the present room, disconnected from a reliable, collective understanding/participation, I lost a structure to the way things were. I lost my metaphysics, the way I understood the world.

I balked at reading. If you know me, you know that reading has a large part to do with who I am, how I become, how I give back. That sort of stopped at the pandemic’s beginning.

Wonder-fully, it was a book on gardening that started me up again. That first summer of the pandemic, when the numbers had settled, we took a road trip to an AirBnB on the side of a Fingerlake in New York, a way to get out of our own house and the dull rigor quarantine had imposed. We picked a place we were familiar with, knew enough about to know we could keep our pandemic-safe practices, and headed out. I packed a stack of books, of course, though I probably wondered why at the time. I wasn’t reading. One of those books was Katherine White’s Onward and Upward in the Garden.

Clifftop overlooking Seneca Lake, the rustic house we stayed in had a garden, and in that a metal table surrounded by chairs. It was there I cracked open this book. I fell into its pages, its way of seeing and saying. It is a marvel. A New Yorker editor writes reviews of seed catalogues in their heyday. How could that be interesting, and why is it three hundred some pages? Every season as the catalogues came to her, Ms. White would read and review the writing, which had a literary pedigree back then. Gardeners of the world delighted; readers of the New Yorker were charmed. It is charming, bewitching, settling, especially if you look up from its pages into a garden surrounding you as you read, realizing you are in the midst of a season and its beauty and being: things are doing what they are supposed to do. Count on them. The repeating cycles of Nature. Reassuring.

Reading through the book, the years of seed catalogues, the pattern of one season after another, I shifted into a kind of Taoist appreciation of what was going on in my moment. Life from one year to the next no matter what is going on, the cliched ‘going with the flow’. Life energy moving through time, maybe not unconcerned with its particular season, but carrying on and through it, doing what life does: being and becoming. Rising to the occasion. This really was reassuring. The dread at being in the beginning of a pandemic, illness and death sweeping through, a steeped uncertainty with everything on hold, abated, and I looked to the larger patterns of Nature, the persistent force that moves through time.

It was the right book at the right time, and it helped me settle back into words, into reading, and rely on patterns of understanding that we carry along even through strife. I look to books in a know-that-you-know-nothing kind of way, hoping to learn something about being, place, and existence. This book helped me regain a sense of possible again. Odd, but there you go.

While I won’t say I am reading again at pace, I am reading more each month. I am a few books into the year already. At the moment, I am in the midst of the appropriately named Begin Again (Eddie S. Glaude Jr., 2020), what James Baldwin has to tell us about our particular time (what a book it is! but that is a different post — hoping to find the words soon to write it, but it is sending me off to read more and all of the Baldwin, and it may be a awhile).

We are still in the midst of the pandemic’s waves — they do drag on, and enough already — but we do seem to be adapting to the situation, carrying on like gardens do and remind us to do, relying on that kind of structural knowing and persistence. What a privilege reading is. While it is a frustration not to be in a mind to read for me, it is also a bit selfish and a whine to go on about it — apologies for that. Know that I am grateful for your attention. Dear reader, what books have helped you settle through these unsettling years and why?

Happy reading,

Tim Singleton

Board Co-chair, HoCoPoLitSo

I’ll point out that Onward and Upward in the Garden deserves another kind of look, one less sentimental, the privilege of property and place offering a different, more critical regard. A post for another day. I talk of words and language as connective above, but Begin Again looks at how they do quite the opposite, as well. It is one of the reasons I put these two together here — there is so much more to reading than just the book you are in, than the perspective you bring to it, all things considered.

writers who dare to be Asian

a blog post by Laura Yoo

When I was growing up or even when I went to college and graduate school to study literature, I did not have exposure or access to Asian or Asian-American writers, thinkers, or scholars. My literary repertoire was almost exclusively white British and American writers. My area of focus was the 18th century British novel.

In graduate school, I started taking courses in African-American literature, so my education in race came through writers like Toni Morrison, Alice Walker, and James Baldwin. Later, I turned to contemporary writers like Tyehimba Jess, Claudia Rankine, and Ta-Nehisi Coates. These powerful voices of African-American writers were my introduction to thinking through my own racial identity, about being a person of color in America.

Maybe it was the getting-older and becoming more aware of my identity and my place in the world, but I realized that I wanted a more focused, specialized language to think about being Asian in America – our history, culture, and language. Of course there is diversity in Asianness, for “Asian” is not homogeneous. And so my reading list has been drilling down to more specific voices: from Asian-American, to Korean-American, to Korean-American women. I am craving voices that sound as much like me as possible.

Laura (right) walking with Marilyn Chin (left) between sessions at the 2018 Blackbird Poetry Festival at Howard Community College

Meeting poet Marilyn Chin changed everything for me. I saw her read on that big NJPAC stage at the Dodge Poetry Festival in 2017 and met her at the Blackbird Poetry Festival at Howard Community College in 2018. Her poetry and my conversations with her (yes, I had conversations with her – that’s right – and she called me “my sister!” and hugged me) opened my ears to that Asian-American literary voice that I didn’t know I craved. I said to my friend after meeting Chin: “She’s so brazenly Asian-American.” I had never read literature like Ms. Chin’s Revenge of the Mooncake Vixen. Like, what? Who gave you permission to write like this? She did, of course. She gave herself permission and she did it. And her poetry dared me to be Asian too.

More recently, I came across another writer who is brazenly Asian in her writing: Cathy Park Hong. Her book, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, is like nothing I have ever read. In this book, she covers a lot of different topics from history, art, cultural commentary, gender, language, poetry, friendship, family, and love – all through a perspective and voice that are brazenly Asian. Some of it so Korean. It seems like the book is written for me and to me. Hong’s book explains to me why I’m drawn to African American literature, why I feel so hyper-visible and invisible at the same time, why I’m connected to Korea though I haven’t set foot in that country since 1989, and why I feel the way I do toward my mother. As Hong asks, “Does an Asian American narrative always have to return to the mother?” Apparently so.

Hong says, at the end of Minor Feelings, “I want to destroy the universal. I want to rip it down.” And this explains why I want to read books about my people. I’m now reading to learn about myself, not just about how other people live or what other people think. I want to read writers who know me, my family, my language, and my experiences as a Korean and an Asian-American. I want to read works that reflect back to me who I am. I want to read books that explain to me things that happened to me and are happening to me. Specifically.

the art of characterization – a reflection on the bauder student workshop

a blog post by Suhani Khosla

As a reader, loving characters that are born from good writing is easy for me. I rooted for Frances Janvier in Radio Silence, mourned Lydia Lee from Everything I Never Told You, and laughed with Pip from Enid Blyton’s classics. I am awed that every tiny reaction of the hundreds of characters I’ve come across had the potential to alter their respective stories.

As a reader, loving characters that are born from good writing is easy for me. I rooted for Frances Janvier in Radio Silence, mourned Lydia Lee from Everything I Never Told You, and laughed with Pip from Enid Blyton’s classics. I am awed that every tiny reaction of the hundreds of characters I’ve come across had the potential to alter their respective stories.

As a writer, though, it is always challenging to build admirable characters: either their initial personality is too shallow, or my descriptions veer helplessly into unnecessary ramblings.

At Friday Black Bauder Student Workshop on March 4th held by Howard Community College, Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah and Tope Folarin taught me the ins-and-outs of characterization. By the end of the workshop, I saw how these strategies meshed and intertwined with Friday Black’s narratives: through the framework of Adjei-Brenyah’s characters, I was able to fully understand prejudice, such anger, and such resilience.

Adjei-Brenyah and Folarin first began with the different types of characterization, engaging the participants from the get-go with creative examples of each. As we went through the modes of characterization (expository, description, and action), the chat blew up with participant’s replies and examples. I saw the benefits of all methods, and some of the drawbacks: expository was a simple explanation, quick and to the point, but only an explanation; description almost forced a perception of the character, yet description called for artful word choice that would lift the passage; and through recording action readers could form a “nuanced view” without influence by the narrator’s voice, yet it could pose the threat of being too vague.

All avenues were used in the final activity, just as Adjei-Brenyah employs them in his writing. We were instructed to create a hero (or an anti-hero) with the following set of questions:

- What is their power/ability that makes them special? Why?

- How did they get the ability?

- What does your character want (initially)?

- Who might try to stop them?

And based on our answers, we used the modes of characterization to create our heroes/anti-heroes. I found it easier and fun to craft a character succinctly, a character that, maybe one day, could stand with the famous and the infamous ones that shaped my life thus far.

Through workshops with engaging repartee among the hosts and participants, students like myself can gather the tools to add layers of depth to their writing. Crafting our individual narratives relies deeply on how we present ourselves and those around us, a process Adjei-Brenyah and Folarin taught us effortlessly. Happy writing!

To watch Adjei-Brenya’s Bauder lecture, make sure to visit https://vimeo.com/showcase/8082121?video=507368937

———————————————————–

Suhani Khosla is a senior at Atholton High School. She likes to read, draw, and write during her free time. She is currently reading Simon Sebag Montefiore’s biography on Jerusalem and Friday Black. Suhani loves working with HoCoPoLitSo as a Bauder Student On Board member, and she hopes to continue her interest in the arts in college.

mana’s musings – international women’s day edition

a blog post by Laura Yoo

The Women I Don’t Know

Last year when I was writing the syllabus for my women’s literature course, I wondered about the “women” part of that course name. What is “woman” and who should be included in this reading list?

As I flipped through the textbook, The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: Traditions in English, I tried to compose a reading list that was diverse. Immediately I saw the gaps in the anthology. Among those missing or underrepresented were African women writers and transgender women writers. I recognized, too, that it’s not just Norton – there are gaps in my own encounter with women’s stories from diverse walks of life and backgrounds. I know so little about these women.

And when I don’t know something, I go and read. But what do I read? Who do I read?

Transgender Women Writers

In the opening of their article “Toward Creating Trans Literary Canon” RL Goldberg is in a situation similar to mine – teaching a course called “Masculinity in Literature” and wondering what we mean by masculine. Goldberg’s students are incarcerated twenty something men who are working toward a college degree. Interestingly, the debate among the students is not over words like “transgender, transsexual, agender, two-spirit, trans woman, bigender, trans man, FTM, MTF, boi, femme, soft butch, cisgender” – these, the students understood. However, “What was contentious: man and woman,” Goldberg shares. This makes complete sense. Of course, it’s words that we think we know, words that seem so clearly opposite, that we must grapple with because they evolve.

In keeping with defying or moving across the spectrum of categories, whether that’s genre or gender, Goldberg includes in their list of works for recommendation Freshwater (about being an obenje) by Akwaeke Emezi and Mucus in My Pineal Gland (“displacing or disregarding genre or gender”) by Juliana Huxtable.

In “12 of the Best Books by Trans Authors That You Need to Read” Torrey Peters (her own novel is called Detransition, Baby) includes these works that show a range in genre and themes: The Unkindness of Ghosts by River Solomon (a science fiction novel that explores structural racism) and Fairest by Meredith Talusan (memoir of Filipino boy with albinism coming to America who is mistaken for white and becomes a woman).

African Women Writers

When it comes to African women writers, we come across incredible diversity among them as Africa is a big place with long, complex histories – with many different languages and cultures. This article from The Guardian, “My year of reading African women, by Gary Youngue” is an excellent introduction for novice readers of African women writers. Youngue’s reading list includes the following:

- Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi

- Kintu by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

- The Secret Lives of Baga Segi’s Wives by Lola Shoneyin

- Stay with Me by Ayobami Adebayo

- The Map of Love by Ahdaf Soueif

- The Memory of Love by Aminatta Forna

- We Need New Names by NoViolet Bulawayo

- Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue

- Beneath the Lion’s Gaze by Maaza Mengiste

- The Moor’s Account by Laila Lalami

And I recommend that you read Youngue’s article for his take on what these works offer us.

This article from Electric Literature, “10 Books by African Women Rewriting History” by Carey Baraka, includes these contemporary recommendations: Dust by Yvonne Adhiambo (set in 2008 Kenyan presidential election), The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah (set in Northern Ghana during pre-colonial times), and The Old Drift by Namwali Serpell (focusing on a Zambian space program).

Expanding Our Sphere of Reading

I know these are incomplete lists, and lists like these reflect the personal as well as the cultural tastes of the one creating the list. And all these recommendations are limited to those authors writing in English. Also, I know that when I look for “transgender women writers” I may be excluding – or drawing lines that exclude – nonbinary and gender nonconforming writers.

As an Asian American woman, I have been diving into Asian American literature lately, particularly those by women. I recommend The Prince of Mournful Thoughts and Other Stories by Caroline Kim (short story collection) and Your House Will Pay by Steph Cha (set against the 1992 LA Riots). It has been so exciting, after so many years of being a student and teacher of literature, to finally discover writers and read books by and about Asian Americans. To open a book and witness stories that I recognize is a certain kind of gift that representation brings.

However, we also turn to books to see the world through others’ eyes. So, if there’s a blind spot in your literary journey (and your blind spot will be different from mine), take a ride with some of the women writers you don’t yet know on this International Women’s Day.

Behind the Scenes of the Poetry Moment Series

We’ve all been swirling around in the frenetic cloud of crazy that has been the last twelve months. For HoCoPoLitSo, one thing has settled out of the hubbub. Poetry is something that helps. Hearing poetry, reading verse, listening to another soul speak truth is a balm.

National Poet Laureate Joy Harjo explains it well.

“When I began to listen to poetry, it’s when I began to listen to the stones, and I began to listen to what the clouds had to say, and I began to listen to other. And I think, most importantly for all of us, then you begin to learn to listen to the soul, the soul of yourself in here, which is also the soul of everyone else.”

If there’s any time we need to listen to our souls, and to the souls of other folk, it’s now.

The Poetry Moment series was created as a response both to the pandemic and to the Black Lives Matter movement. Since 1974, HoCoPoLitSo has been deliberate in its inclusion of authors to represent the fullest range of human experience. We have long believed that opening a book, reading a poem, or attending a literary event can be a powerful humanistic journey of exploration, education, and enlightenment.

The project evolved from a broad-based poetry video series to focus for the first eleven weeks on amplifying the voices of Black poets who have visited our audiences. Later, we added the voices of poets of different backgrounds.

And in November, we started videotaping young actors from Howard Community College’s Arts Collective reading introductions to the archival video of poets and their work. Directed by Arts Collective’s Sue Kramer, these actors–Chania Hudson, Sarah Luckadoo, and Shawn Sebastian Naar–spent many Monday evenings learning about poetry, tripping over tricky names, and recording video introductions that help explain the poems to viewers. They handled their own styling, and even set up their own lighting and sets.

I asked the actors a few questions about the project and its evolution, and loved their responses. Naar, who portrayed Langston Hughes for HoCoPoLitSo’s 2019 Harlem Renaissance Speakeasy, has taken on roles for Spotlighter’s, Wooly Mammoth, Howard University, and the Kennedy Center. Hudson, who was the Harlem Renaissance Gwendolyn Bennett, is receiving her bachelor in fine arts from UMBC this spring in theater, and has played in many Arts Collective shows, as well as performances at UMBC and Rep Stage. Sarah Luckadoo is an actor, choreographer, movement coach, and teaching artist who has worked with the equity company Ozark Actors Theatre in Missouri, Red Branch Theatre Co., Laurel Mill Playhouse, HCC’s theater department, and of course Arts Collective.

The enthusiasm these actors brought to their work gave me such hope, and reminded me of when the 22-year-old inaugural poet Amanda Gorman read her uplifting lines on January 20:

We will not march back/

to what was/

but move to what shall be/

A country that is bruised but whole …

Perhaps watching a Poetry Moment featuring these young actors and the master poets will let a poem will take up residence in your bruised heart, and help you through the chaotic, difficult times ahead.

HoCoPoLitSo: Had you ever read poetry before?

Shawn Sebastian Naar: I have read poetry for performances (Langston Hughes, Shakespeare, Amiri Baraka, etc.) and I have read poetry recreationally for enjoyment (Maya Angelou, Shakespeare, Rupi Kaur, etc.)

Sarah Luckadoo: Yes! I was introduced to poetry at an early age and have always found myself drawn to it. My theater teacher in high school, who was also a published poet, was the driving force behind that love. Most, if not all, of the theater projects we did had some sort of poetry involved, including participating in the poetry recitation competition, Poetry Out Loud.

Chania Hudson: Yes! I’ve read poetry for HoCoPoLitSo and Arts Collective’s Harlem Renaissance event as Gwendolyn Bennett, and recently I read a few poems as Audre Lorde for Howard Community College’s Women’s Studies Salon: The Power Within virtual event.

HCPLS: If you did read poetry before, did you enjoy it?

SL: 100%! I love that poetry has this unique ability to tell full, intricate stories through its varying structures or even just a few words. It really shows how truly powerful words can be.

CH: Yes, I love reading poetry! I’ve found some of my favorite poems through working with HoCoPoLitSo.

SSN: Yes, I enjoy reading poetry. Reading great poetry is like listening to great music. When a poem or a song hits me in the right way and expresses a universal truth, it resonates deeply, and I am moved to tears or fits of laughter in the moment.

HCPLS: Did your perceptions of poetry change as we went through the project?

CH: I’ve always had a respect and love for poetry but this project turned my attention to the poet, and understanding the WHY of their poetry. It has felt like a behind the scenes look at how and why poems come to be.

SSN: Before this project, my personal selection of poetry was limited to more well-known poets or poets from school. Through this process, I’ve found some new favorite hidden gem poems, I’ve been introduced to Poet Laureates, and I even have some international poets that I’ve fallen in love with (Seamus Heaney, I’m looking at you).

SL: I’ve always enjoyed poetry, but this process has reignited the love I had for it. I hate to admit it, but I forgot what it felt like to just sit and read or listen to poetry. With the busyness from day to day and this “go go go” mentality, I’ve had a separation from it and this project made me realize how much I miss it.

HCPLS: Was there a favorite poem that you worked on (and why)?

SL: Such a hard question! I’ve honestly loved all of the poems I’ve worked on, but if I had to pick favorites it would probably be “blake” by Lucille Clifton and “Beijing Spring” by Marilyn Chin. “blake” was one of those poems that just reached out and grabbed me from the get-go … the words, the story, all of it. And I appreciated it even more when I discovered why Lucille Clifton wrote it and what she was trying to say. For “Beijing Spring” I particularly connected with it because of Marilyn Chin’s message of youth empowerment. She focuses on the innocence and determination of youth throughout history and demonstrates how they can quite literally move mountains to create change and defend their democratic rights.

CH: “Mrs. Wei Wants to Believe the First Amendment” by Hilary Tham, because it introduced me to a new perspective that I wasn’t fully aware of before reading it.

SSN: It’s tough to single out a favorite, but a couple poems of note would have to be Amiri Baraka’s “In the Tradition” and Josephine Jacobsen’s “Gentle Reader.” Baraka is one of my favorite playwrights and poets. The intensity of the passion and fire of “In the Tradition” is special. Conversely, I had never heard of Josephine Jacobsen before this project, but I love how she plays with opposites in “Gentle Reader.” The language is sensual, and the poem is sexy. Not what I expected at all from the refined Jacobsen and that is exactly what makes the poem brilliant.

HCPLS: Was there something you came across in the project that will stay with you?

CH: The majority of the poems featured will stay with me because of the way these poets have impacted their communities and the world around them. Each poem was like seeing the world through someone else’s eyes and I know that will stick with me for a while.

SSN: It feels to me that poetry gets overlooked sometimes in the arts. I’ve come across an incredible array of poets in this project and what will stay with me is the appetite for great poetry of the past, present, and future.

SL: In such an unprecedented time, it can be difficult to feel inspired or remember what good is left in the world. This project did both of those things. These poets shared stories about places, people, their lives–the good and the bad all wrapped together. What will stay with me is not only their stories, but their willingness to be vulnerable and share them. At the end of the day, we all have something to share, something to contribute and that’s pretty special.

Susan Thornton Hobby

Poetry Moment series producer

Click here to view Poetry Moments online at the Columbia Arts Channel.

Up next for the Arts Collective is their What Improv Group! and “A Valentine Affair (from afar).”

alone in a zooming crowd

a blog post by Laura Yoo

In the time before quarantine – do you remember? – people used to sit in a room together for readings. We shared a physical space and we were there not only in mind but also in body. When a poem was read, we reacted. We observed the small changes in each other’s bodies: tilting of the head, rigorous nodding, maybe a rolling tear, or uncrossing then recrossing of the legs. Maybe a faint smile or an uncomfortable cough. Maybe a small sound – like “oof” or “whew” or “wow” – escaping our mouths involuntarily. Maybe two strangers’ eyes would meet – and maybe they’d smile or raise an eyebrow in agreement. Then, having experienced the reading together, friends or strangers might stand around the refreshments table or stand in line for the book-signing and debrief: What did you think? I didn’t expect that! I loved that one poem about… I am thinking about that line…

In the time of COVID, attending readings is a very different experience. I’m alone in the bedroom with a glass of wine. That’s it: me, wine, and computer screen. Most of these virtual events show only the author and the moderator (for a good reason) and there is little or no interaction. If I make faces or a gasp escapes my mouth, it’s just for me. Sometimes I cry alone. Other times I laugh and snort all to myself. I might hop online to order a copy of the author’s book even as they’re still reading. I might text my husband to please bring me more wine. It’s a solitary experience.

If a friend is also joining the reading from the comfort of her own home with her own glass of wine, we might text each other. Instead of exchanging looks, we exchange emojis, maybe a “WTF” or an “OMG”. But this isn’t always possible – sometimes it’s work, sometimes it’s kids’ meal times or bed times, and sometimes it’s just that there is nothing left to give at the end of a COVID-day.

Recently I was in a virtual open mic reading when a debate arose: one of the poets read a poem in which he uses the n-word and one person in the audience shared in the chat that they were offended. The moderators responded, then the poet addressed the issue – about how and why he’s using the word. I wished I could hear that audience member’s voice and see their face. What would I have heard or seen? Anger? Sadness? Pain? I also wished I could turn to a friend or a stranger and look for a reaction. I wished I could stand by the refreshments table and ask, “So what did you make of that?” Instead, I emailed a few friends about it and we met a couple of days later on Zoom to chat about it. That led to an important conversation about who, what, where, when, why, and how of the n-word in poetry. And that was good. Still. What I missed was the opportunity to commune with others spontaneously, the chance to exchange looks and ideas with each other as it was unfolding.

In the “before time,” why did people even go to poetry readings? We can find an endless supply of videos of writers’ readings, talks, performances, and lectures online. Still, we got tickets, we got babysitters, we drove, we got ourselves to places on time, we found our seats, and we sat with others to listen. We made dinner reservations or post-reading drinking plans. What was all that for? For the community. For the shared sound of language. For the faces. For the movement of bodies. For the physical proximity to the creators of art. For the reaction from and discussions with other patrons of art.

I miss people. I miss sharing space with people. But I realize it’s a trade off. And I have a feeling that even when we “go back” we may never go back to the way we used to do things, including literary readings. And maybe that’s not a bad thing.

I am grateful that we could eavesdrop on Eula Biss’s (Having and Being Had) conversation with Cathy Hong Park (Minor Feelings). What an incredible opportunity it was to listen to Ibram X. Kendi (How to be an Antiracist) along with 1000 other people. When Claudia Rankine and Robin DiAngelo had a conversation about Just Us for New York’s 92Y, everyone with a link (and $15) could watch. How cool that Purdue Creative Writing presented Cameron Awkward-Rich (Dispatch) and Franny Choi (Soft Science) and made the registration open to the public and free. Even though Frances Cha, the author of If I Had Your Face, was at her home in Korea, she could have a conversation with Eun Yang (NBC news anchor in Washington, D.C.) at 7 p.m. on a Friday evening (EST). It was 8 a.m. in Korea.

In this time of stress and uncertainty, having access to art virtually significantly improves the quality of my life. And I am grateful for that.

So, I hope you will join me at some of these virtual events that are coming up.

- Sunday, September 27, 2020: The Creative Process

Wednesday, September 30, 2020: Inclusion

Sunday, October 4, 2020: Representation- Time(s): 7:00pm – 8:30pm

- Hosted by Howard Community College’s Arts Collective and Howard County Poetry and Literature Society

- Friday, October 2, 2020

- Time: 7:30pm

- Jose Ross reads from his new work Raising King

- Introduction by E. Ethelbert Miller

- Hosted by Howard County Poetry and Literature Society

Conversation with Lisa See (The Island of Sea Women)

- Tuesday, October 6, 2020

- Time: 11:00 am

- Conversation host: Laura Yoo (yeah, that’s me!)

- Hosted by Maryland Humanities One Maryland One Book and Howard County Library System in partnership with Howard County Poetry and Literature Society